'The Measure of Forgiveness'—Parable of the Unmerciful Servant

If we ask to be forgiven our trespasses 'as' we forgive others, then we are asking not to be forgiven if we ourselves are unmerciful.

If we ask to be forgiven our trespasses 'as' we forgive others, then we are asking not to be forgiven if we ourselves are unmerciful.

In this chapter…

What will happen to us if we are unmerciful—and why

How our enemies are our greatest benefactors

The more subtle meanings of this parable hidden beneath the surface.

See also:

'The Measure of Forgiveness'

From

The Preaching of the Cross, Part I

Fr Henry James Coleridge, 1886, 159-70

St. Matthew xviii. 21-35; Story of the Gospels, § 88

(Read at Holy Mass on the Twenty-first Sunday after Pentecost)

Connection of the discourse—St Peter’s question

ALTHOUGH nothing had been said in the course of the last discourse on our Lord concerning the forgiveness of injuries, still the subject of such forgiveness lies very close to that of the remonstrance with one who has injured another, and with the general tone of that instruction.

Thus it is not surprising that the question asked by St. Peter should have been connected in the mind of St. Matthew with the other subjects lately discussed, even if the question itself was not put by the Apostle to our Lord at the very same time with the former discussion. It may certainly be assumed that the interval of time was not long between the discourse of which we have been speaking, and the question as to forgiveness and the beautiful parable with which our Lord answered it.

Then came Peter unto Him, and said, ‘Lord, how often shall my brother offend against me, and I forgive him? till seven times?’

The parable of the unmerciful servant

Jesus saith to him:

‘I say not unto thee till seven times, but till seventy times seven times.

‘Therefore is the Kingdom of Heaven likened unto a king, who would take account of his servants. And when he had begun to take the account, one was brought to him that owed him ten thousand talents. And as he had not wherewith to pay it, his lord commanded that he should be sold, and his wife and children, and all that he had, and payment to be made.

‘But that servant falling down, besought him, saying, Have patience with me and I will pay thee all. And the lord of that servant being moved with pity, let him go and forgave him the debt.

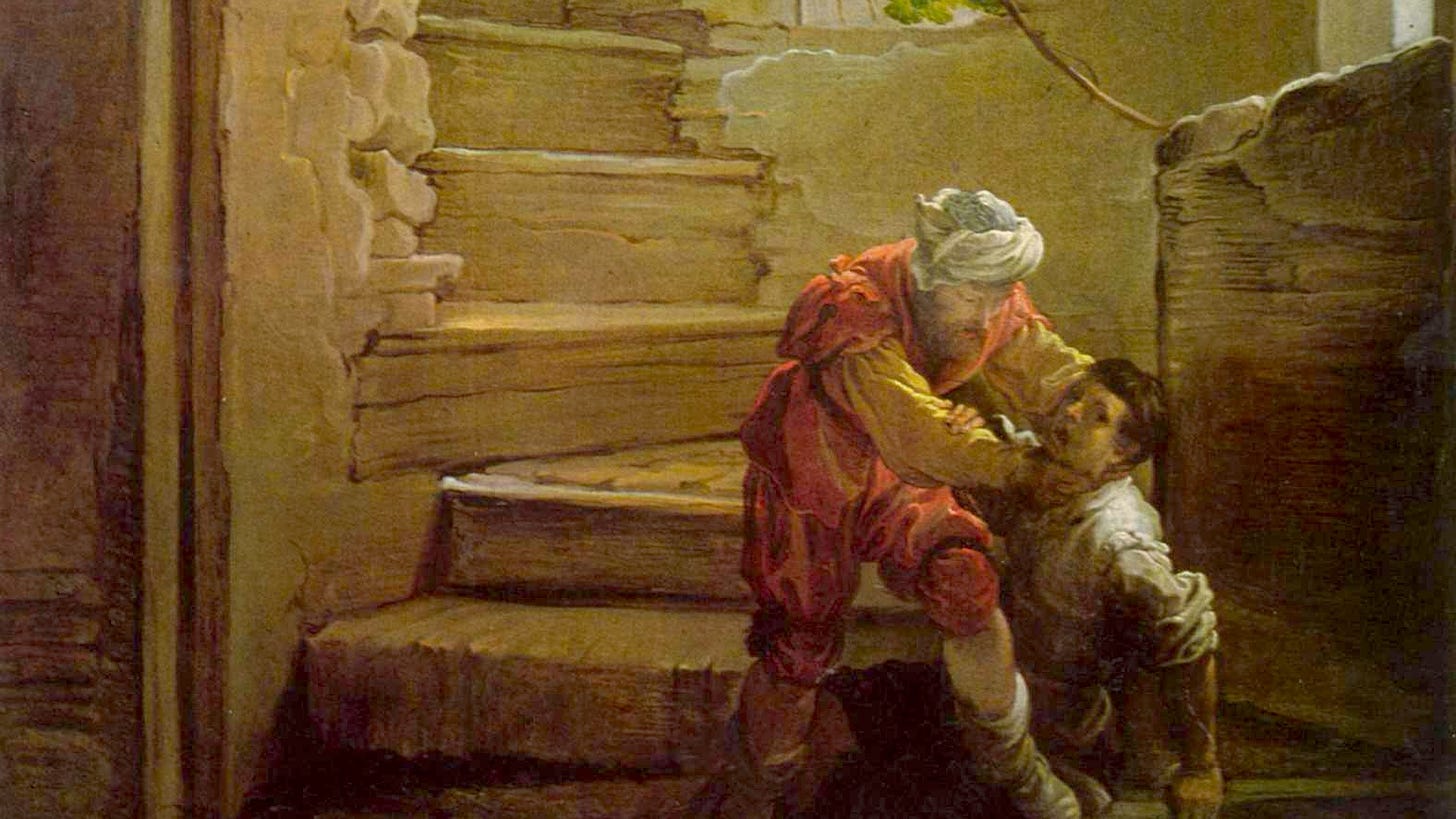

‘But when that servant was gone out, he found one of his fellow-servants that owed him a hundred pence, and laying hold of him, he throttled him, saying, Pay what thou owest! And his fellow-servant, falling down, besought him, saying, Have patience with me and I will pay thee all. And he would not, but went and cast him into prison till he paid the debt.

‘Now, his fellow-servants seeing what was done, were very much grieved, and they came and told their lord all that was done. Then his lord called him, and said to him, Thou wicked servant! I forgave thee all the debt because thou besoughtest me. Shouldest not thou then have had compassion on thy fellow-servant, even as I had compassion on thee?

‘And his lord being angry delivered him to the torturers until he paid all the debt. So also shall My Heavenly Father do to you, if you forgive not every one his brother from your hearts.’

The mercifulness of God

This beautiful parable sets before us one side of the mercifulness which is characteristic of God, and the imitation of which He insists on almost more urgently than anything else in those whom He makes His children in this world.

The side of this gracious attribute which is here exhibited is chosen by our Lord on account of the question asked him by St. Peter, which referred to the forgiveness of injuries to a brother. For forgiveness of debts and injuries is mercy exercised in one particular way.

We see the other side of the same attribute in such parables as those of the good Samaritan or the ten virgins. In those others the part of God’s mercifulness which is selected for display is the compassion on afflictions of every kind, whereas here, as has been said, it is the peculiar act of mercy which consists in the forgiveness of offences. For the mercifulness of God, even as far as it can be imitated by us, exercises itself in a great many various ways.

Clause in the Lord’s Prayer

But, again, our Lord is led by the form of the question put to Him, to speak directly rather of the obligation of the practice of perfect forgiveness than of the enormous blessings which are involved in that virtue, and which ought to make us welcome every occasion of its practice as the finding of a great treasure, rather than submit to the use of such occasions as a duty. Our Lord bids us pray daily, ‘Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.’

Thus He bids us take into our mind and heart, whenever we repeat His Prayer, all the offences which we may have received, of every kind, as well as all those that we may have committed, and by the perfect forgiveness of the first fit ourselves to gain the perfect obliteration of the obligations we have incurred by the second. Thus we are continually to practise our souls in this Divine virtue, especially in order that we may continually receive the pardon which God bestows on us for its exercise.

This is what He means when He says, ‘When you shall stand to pray, forgive if you have ought against any man, that your Father also Who is in Heaven may forgive you your sins.’1 The teaching of this parable is precisely the same, but it is put in a different way. Instead of teaching us that if we want to be forgiven we must make an act of universal forgiveness before we ask for our own pardon, our Lord here tells us that our own pardon will be cancelled and reversed if we do not from our hearts forgive whatever we may have to forgive.

Details of the parable—repetition of the same offence

The parable is so simple in its obvious meaning that it hardly requires much explanation. But there is always in these parables of our Lord a question as to the signification of the particular details, apart from the general scope of the parable, which is plain to all. And in this case there are some few points on which it may be worth our while to inquire how far they may have a special meaning of their own.

The question of St. Peter, as has been said, was probably suggested by the general tenour of the doctrine which our Lord had been laying down. The Apostle thought it a very great thing indeed to propose that he should forgive his brother seven times over. Indeed there are very few men who would ordinarily go so far in the way of condonation of the same offence, and the mass of mankind would probably find something to blame, at least in a parent or a superior of any degree, who passed over the repetition of the same offence so many times as seven.

But it is not necessary to suppose that there is question here only of the repeated forgiveness of the same repeated offence. Our Lord does not teach that superiors or parents are to forgive offences which are not repented of, or to forbear even from wholesome punishment in cases where that may seem to be needed for the emendation of the offender, or as an example to others for the due maintenance of discipline and virtue.

There are in such cases principles involved peculiar to themselves. An offence may be forgiven from the heart which yet it may be a duty to punish externally, as the sin of David in the matter of Uriah was visited on him by God, first by the death of the child born to him, and afterwards by the chastisement which he underwent in the rebellion of Absalom, and in other ways.

But the majority of men would think that with whatever amount of sincerity the pardon of the same offence was sought at their hands over and over again, there must be some limit to their forgiveness, and few would go beyond St. Peter with his seven times, even if they went so far.

It is, of course, not so difficult to have a habit of perpetually forgiving, when there is not the additional circumstance of the repetition of faults several times forgiven, and it seems to be this habit of which our Lord is here speaking, the habit of most gladly and heartily welcoming as a great blessing every occasion of forgiveness which presents itself to us, as men bent on the acquirement of wealth hail with the greatest eagerness every occasion of enriching themselves more and more.

The habit of forgiving—the point of the parable

Our Lord’s answer of seventy times seven must be understood as simply indicating that there is to be no limit whatever, that the number of times of the occurrence of the offence must have nothing to do with the question of its condonation.

The Divine reason for this is contained in the truth which is represented in the parable by the forgiving of the debt of ten thousand talents by the King. This truth is that we are debtors to God for the pardon of innumerable sins, and that, in consequence, if we are to be His children, and to earn our forgiveness, we must set no limit to our repeated forgiveness of others, who may offend against ourselves.

The proportion, or rather the impossibility of there being any proportion, between the offences in which we are debtors to God, and the cases in which men are, as it were, debtors to us, is represented in the parable by the proportion between the ten thousand talents on the one hand and the hundred pence on the other.

It is easy to see that the image used in the parable is utterly inadequate to sustain the comparison. For there can be no offence against man which can be compared in gravity with any offences which we commit against God.

The truth that God makes our forgiveness of others the condition and the measure of our pardon by Him, as we are taught by the very wording of the Lord’s Prayer, is touched in the parable by the significant feature, that the words in which the fellow-servant of the man who has been forgiven by his lord pleads for patience, are identical with those used by that man to his lord in the first instance.

The enforcement on the part of God of the condition of forgiveness of others, if we are to hope for forgiveness from Him, is the main point of the parable, just as in the description of the separation of men at the judgment day as the sheep are separated from the goats, in the last of our Lord’s parables, the connection between the practice of the works of mercy here and the eternal rewards which are to be allotted at that last day, is the main point of that teaching.

The points as to which there may be some doubt or difficulty in the details of this parable are easily seen, and we may pause a moment to say a few words with regard to each of these.

The fellow servants

In the first place, then, it may create some difficulty that it is said in the parable that, when the unmerciful servant had treated his debtor so cruelly and in a manner which displayed so much ingratitude to his own lord, ‘His fellow-servants seeing what was done, were very much grieved, and they came and told their lord what had been done.’

It is not probable that our Lord could mean here that the fellow-servants of Christians will make complaints against them to God, at least in the way of demanding vengeance and bringing an accusation against the offender. Thus this circumstance seems at first sight merely an ornament and embellishment in the parable, without anything in truth corresponding to it.

But it may be meant that any want of perfect charity between man and man, especially between servants of the same lord, as is the case with Christians, or between persons belonging to different classes of society in mutual relation one with the other, is an injury to society and to the Church as such, and therefore a cause of pain and scandal to all good and loving members of the same, who have the interests of the community at heart.

An act like that of the unmerciful servant has a direct tendency to destroy the peace of the Church, to bring down chastisements upon society, to separate class from class, to cool mutual love and confidence, and to impede the force of Christian prayer. Let us dwell for a moment on the considerations thus suggested.

Every one is edified and every one is blessed when charitable and merciful practices prevail. But although the saints of God and the holy Angels would not complain to Him in any angry spirit against offenders against charity, they might well be moved to pray very earnestly for the conversion of such offenders and the redress of the hardship. Their prayers might have the effect of bringing about, in the Providential order of things, some visitation on the sinner, which might issue in his conversion and in the relief of the poor sufferer from his severity.

And if God sent some chastisement, in the course of His Providence, on the home or the family of the ungrateful man, that would not be simply as a measure of vengeance and of anger. It would be rather, as all chastisements inflicted in this world are, ordained by and tempered with mercy, and a direct appeal to him to enter into himself, and so obtain once more the pardon of his fault. For it is constantly the way of God to plague those who have offended Him, especially in any scandalous way, by affliction which visits their homes and families, as if to make them consider what it is that they have done to bring down on them the anger of God.

In this sense we may understand the complaint of the fellow-servants, as well as the chastisement which is spoken of in the parable as inflicted on the unmerciful servant, as when it is said, that the lord being angry delivered him to the torturers until he paid all the debt.

Punishment of the unmerciful

Another point as to which question may be raised with regard to the details of the parable is contained in the passage in which it is said that the unmerciful servant is handed over by his lord to the punishment, or rather, the torture which he might have undergone, if his own lord had been equally unmerciful to him in the first instance. He is treated, according to the story, as if he had never been forgiven.

It has been thought by some that this implies that when we fall into sin afresh, the pardon already accorded to us for past sins which have been confessed is altogether cancelled, and we become once again victims of the wrath of God, not only for the sin which has brought on us this renewed anger of God, but also for all others that we have ever committed, even though they may have been cancelled by penance and absolution.

It is true that the lord in the parable treats the unmerciful servant in that manner. But even if the doctrine which is meant to be drawn from this parable were to be understood in the strictest sense, in harmony with this detail, it would not follow that the punishment was now inflicted for the former sins. It would only follow that the guilt of the new sin of unmercifulness and ingratitude was heinous enough to deserve and receive punishment equal to the full exaction of the debt.

It may have been, not that the old guilt revived, but that the circumstance of ingratitude and hardness added so much new guilt to the soul, as to make it liable to the punishment which it might have received if the guilt had not been forgiven. Thus any sin, once pardoned, is not revived by the ingratitude of the sinner who refuses to forgive in return the small offences that he may have to forgive.

But this is in itself a great sin, and one which places the soul in a state of damnation, and more, in a state in which it is most difficult for it to obtain fresh forgiveness. For such hardness stops up the very fountain of God’s mercies, which are only promised to us on the condition of our pardoning the offences of others against us.

Ingratitude and unmercifulness

A sinner reciting the Lord’s prayer in this state of heart is really imprecating on himself the merciless anger of God. For he asks to be forgiven as he forgives, and as he does not forgive, he asks not to be forgiven.

It is not the ingratitude which is irremissible, but the unmercifulness. There is always in every sin a large element of ingratitude, and we are probably none of us aware of the immense debt which we owe to God’s justice in this respect. To be fully grateful to God requires an enlightenment and a fervour which are found only in the saints. Unless we know all that we receive day after day, and hour after hour, from God, it is not possible for us to give Him the thanks which He deserves.

Therefore, the admixture of ingratitude in our service to Him is a fault which, in His infinite compassion, He may look on with greater mercy, though St. Paul tells us that one of the chief causes of the miseries to which the heathen world was abandoned was their deep ingratitude to God, as far as they knew Him. But mercifulness requires the most exquisite enlightenment. It ought to be the very air which we breathe, for it is by the mercy of God alone that we are what we are, and have all that we have, and hope for all that we hope for. We can only be unmerciful by forgetting our own relations and position with regard to God, by having false ideas of our own rights and claims, and by utterly ignoring our own need of mercy.

Thus, unmercifulness is inconsistent with the love of God and the love of our neighbour, and is in itself an almost sufficient sign of reprobation. And when a man has just been imploring for himself the mercy of his offended and justly incensed Lord and Master, and has just received from Him the forgiveness of all his debt simply out of compassion, there must be in his heart a revolt and revival of malignity of the blackest kind, if he can turn at once on his brother and refuse him his pardon.

All grace must be swept away from the soul in such cases, and therefore it is that there is no exaggeration in the figure used by our Lord in the parable where He describes the chastisement of this unmerciful servant, as being the exaction of all that he had himself been liable to before he was forgiven.

Our Lord dwelling on the chastisement

We have remarked that it has pleased our Lord in this passage to insist on the duty of forgiveness rather from the terrible motive of the punishments to which we may be exposed by the contrary fault, than by setting before us the innumerable blessings which are placed easily within the reach of those who are careful to practise the merciful and forgiving temper.

Just so He chose, in the passage of which this parable is the continuation, to dwell especially and more than once on the terrible punishment of the scandalous, although He did not altogether omit the immense blessings awaiting those who are careful of His little ones.

The form of our Lord’s teaching may be accounted for by the question of St. Peter. To ask how many times we are to forgive implies that there is to be a limit to our indulgence in this regard. It is not the language of one who looks on every possible occasion of forgiving any one anything as the most blessed of treasures. St. Peter seems to ask what was to be the precise limit put to his practice of a virtue which contained in itself so immense a treasure, as if it were possible for him to be too frequent in forgiving.

Therefore, the duty of forgiveness of his brother was put, by the terms of his question, as if it were more of a duty than a privilege, a thing the practice of which required urging on rather than checking. The true aspect of forgiveness is this which is placed second only in the question before us, and which is implied in the position which this virtue holds in the prayer of our Lord.

Our measure of forgiveness

In very truth, every opportunity of forgiveness of another is a precious gift from the mercifulness of God, putting in our hands the power to bathe ourselves afresh in the life-giving streams of His grace and compassion. It is an occasion on which we are told to take the key of God’s treasures and help ourselves to as much as we will.

Most truly, then, is it said by the Fathers that our enemies and all who injure us are our best benefactors, opening to us opportunities which otherwise we should never have. The teaching of our Lord, when taken into consideration together with the words of His prayer, suggests to us the careful study of every kind of mercifulness, as a skilful householder considers in how many ways and how quickly and most often he may multiply in profitable investments the resources which he has to dispose of.

The measure set before us in our practice of this virtue is simply the relation in which we wish ourselves to stand with God. We wish Him to think of us and deal with us and behave towards us, with the most unclouded confidence and the most perfect affection, without even the slightest remembrance that we have ever offended Him, as also with the most perfect substantial pardon for our offences, without reserve or mistrust, as if we had always been most innocent and most faithful, emptying upon us the choicest boons of His most magnificent beneficence.

All this, and more than we can imagine, more than our most soaring wishes can rise to, it is within our own power to obtain, by the exercise of the privilege of forgiveness to others, in this sense the highest of all the boons which He has placed in our hands, because it is the coin which purchases all boons whatsoever. We have but to carry out into every thought and word and action and feeling towards our neighbour this most perfect charity, and then we may be certain that all which we seek from God will be ours.

From Fr Henry James Coleridge, The Preaching of the Cross, Part I

If you’re enjoying reading Father Coleridge’s rich explanations of the Gospels and the life of Our Lord, then will you lend us a hand and hit subscribe?

Further Reading:

Follow our projects on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

St. Mark xi. 25.