How does the Parable of the Sower unlock all Christ's other parables?

We could even call it the 'parable of parables', as it holds the key to all the rest.

We could even call it the 'parable of parables', as it holds the key to all the rest.

Editor’s Notes

Our Lord told the Parable of the Sower, read on Sexagesima Sunday, early in His public ministry, as He began to teach in parables more frequently. It is the first recorded parable in the Gospels.

It follows growing opposition from the Pharisees and the rejection of His teachings by many, prompting His shift to parabolic instruction.

Shortly after, He explained the meaning of this and other parables to His disciples, emphasising the mysteries of the Kingdom of God. He also explained that he was using this manner of teaching both to reveal truths to those who are disposed to receive them and to conceal them from the hardened-hearted.

In this piece, Fr. Coleridge tells us…

How the parable illustrates how different hearts receive or reject divine truth.

That it reflects the ongoing spiritual battle for souls and the necessity of perseverance in grace.

Why the image of the sower scattering seed evokes Christ’s own mission and that of His Apostles.

He shows us that the fruitfulness of grace depends on the disposition of the soul receiving it.

The Parable of the Sower

The Training of the Apostles Vol. III

Chapter VIII

St. Matt. xiii. 18–23; St. Mark iv. 10–25; St. Luke viii. 9–18;

Story of the Gospels, § 61

Burns and Oates, London, 1884

Headings and some line breaks added.

Sung on Sexagesima Sunday

Part I: How does the Parable of the Sower unlock all Christ's other parables?

Part II: How do the birds reveal a brutal war for the soul in the Parable of the Sower?

Part III: What if your faith is shallow, and you won’t know until it’s too late?

Part IV: What makes for good soil in Christ’s Parable of the Sower?

The first Parable

Enough has already been said to explain the general purpose of our Lord in the parabolic teaching, the first instances of which must now be made the subject of more particular study by us. We shall see how very wide is the range of this teaching, and how it can easily be understood that not all that the Apostles and disciples might learn from it was naturally to be proposed, without some reserve, to the people at large.

Our Lord has been at the pains, not only to explain the first parable at considerable length Himself, but to leave behind Him in the Gospels this explanation, as if to furnish us with certain principles of interpretation for other similar cases, in which we are more or less left to ourselves in the study of His Divine words.

It will be seen that the subject matter of the whole of this series of parables is more or less the same, and, when we come to try to unfold the great treasures of doctrine which it contains, we shall perhaps be no less astonished at the amount of truth which is here condensed and compressed in so small a space than at the details of the parabolic teaching in themselves.

In fact, it would require many volumes to set forth the whole of the riches of Christian truth that were here handed over to the devout consideration of the Christian student in words so few and so simple.

Details easily understood—but not their application

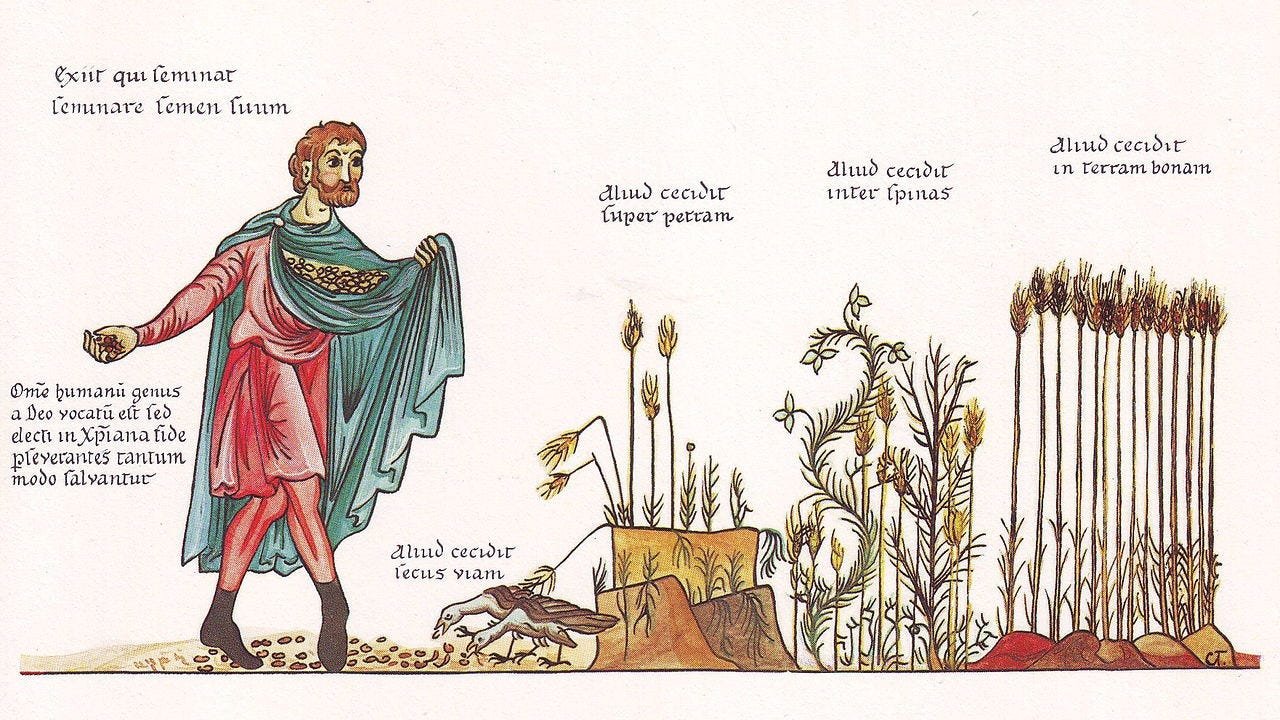

It will be easily remembered that the first parable describes the fate, so to say, of the Divine seed of the Word of God, under the image of the issue of an actual sowing, in the case of which there were four several kinds of seed, or rather, four several results of the committal of the seed to the ground.

In the first case, the seed had not been allowed to remain in the ground at all. In the second case, it had sprung up for a short while, and then had withered away. In the third case, it had sprung up and been choked. In the fourth case alone had it come to maturity and produced its expected fruit, thirty-fold, sixty-fold, a hundred-fold.

The causes of failure in the first three cases had been various. In the one, it had been that the seed had fallen by the wayside or on the footpath, where it had been trodden underfoot or snatched away by the birds of the air. In the second case, it had fallen on stony ground without depth or moisture, and had not been able to withstand the scorching rays of the sun in consequence. In the third case, it had grown up in the midst of thorns, which had sprung up and choked it, depriving it of the moisture and support from the soil which it required.

Here, then, is a sufficient variety of causes of failure, and on the other hand, there is the counterbalancing description of the good soil, the fruitfulness of which is enough to compensate for more failures than those which have been spoken of.

At the same time, it is obvious that a hearer who had only very imperfectly perceived the drift of the parable in our Lord’s mouth must have been stimulated to much anxious questioning as to the several causes of unfruitfulness of which he had heard, and have been eager to know what was represented by the wayside, what by the fowls of the air, what by the stony ground, what by the thorns, and how he could secure for the Divine Word, which was represented by the seed, that happy reception in his own heart which was figured in the prolific return of the good soil.

And, as it must be remembered that the Apostles were now in the course of formation by our Lord for that holy ministry among the souls of men for which they were destined, it is easy to imagine that they also must have been full of speculation and surmise as to the precise meaning of the short but most pregnant parable which they had just heard.

There need be no doubt that the parable was but a simple adaptation to Divine purposes of what was passing before their eyes, perhaps at the very time when the words of our Lord were spoken. The seed time was now come, in what we should call the early winter season, the work of husbandry was in full course, and many of those who listened to the discourse must have had practical acquaintance with the details of which our Lord spoke.

There was no difficulty about understanding so simple a figure, as far as the figure itself went—but what were the verities concealed behind these commonplace details?

Points in God’s action omitted

There are points, as we shall see, in the Divine economy or way of action, to parts of which the present parable refers, which our Lord did not draw out even for the instruction of the disciples.

He did not tell them, for instance, how it is that God has chosen, in imparting His truths to men, to act as a sower of seed rather than in any other manner. He might, for instance, have acted as the planter of trees. He might have planted just as many as He wished to grow.

Or He might have acted as a builder, according to an image which we find used of Him elsewhere in Scripture, who provides all the material of His edifice, and wastes none of it. Again, our Lord spoke here of the ground as having this or that quality, on which He makes the success of the process depend, and He says nothing of the good qualities of the seed itself, or of the sunshine and rain and air which, as a matter of fact, have so large a part in the production of the fertile harvest.

He is describing the various causes of failure, and He does not describe the causes of success except so far as they are left to be inferred from the effects of their opposites.

Still less does our Lord here draw out the very important truths connected with the possible improvement or deterioration of the particular kinds of soil of which He speaks, as how the stony ground may become moist and deep soil, how the thorns may be weeded out, or how the good soil, in its turn, may be turned into the barren.

That there may be changes thus wrought in the conditions under which the seed is received is implied both in the giving of the parable itself and in the words which our Lord subjoins, ‘Take heed how you hear,’ and the rest. But it is the principle of the parabolic teaching that various truths belonging to the same great subject are kept for treatment in several and successive parables, and not often combined in one.

The truth on which our Lord insists, in particular, relates to the various dangers which beset the good seed when it is sown, as it is sown ordinarily, by being scattered broadcast over the world.

Increase in goodness or badness

It may also be remarked at the outset that the conditions of which the parable speaks increase in badness and goodness in an inverse measure—that is, the first condition of the seed which is unfruitful is the worst of all, that in which the prospects of a favourable issue are altogether taken away, for the seed by the wayside is caught away from the heart by the evil spirit.

The condition which comes next in order is that of the seed which grows up and is then withered by the burning heat of the sun, and in that case also, though there has been some progress towards fruitfulness, the further hope is altogether defeated.

The seed thrown among the thorns is in a less unfavourable condition, because there might be a hope of its fruitfulness if the thorns are removed.

In the case of the seed sown on the good soil, the first increase is of thirty-fold, the second of sixty-fold, and the last of a hundred-fold.

Thus, our Lord seems to imply that all the dangers must be avoided successively, and not one alone—the pathside, the fowls of the air, the unprepared soil, the choking thorns—and that even when the seed is fruitful, it may become more fruitful: the thirty-fold become sixty, the sixty a hundred-fold.

The greater part of the seed not wasted

Again, it may be remarked that it is not fairly to be gathered from this parable that the greater part of the seed is wasted.

Although there are three out of the four conditions in which this waste takes place, yet they are not conditions which could naturally be expected to be verified in the case of the greater part of the seed sown by the sower.

In all ordinary circumstances, the great majority of the seed would be thrown on the good and fertile ground, and not on the stony soil, or among the thorns, or by the wayside. And the return of the good seed as stated by our Lord is never less than thirty-fold, while in other cases it reaches as much as a hundred-fold—far more than enough to reward the labour and expenditure of the husbandman, even if he loses some of his grain among the thorns and in the other ways mentioned in the parable.

So far, then, the effect of this parable is not such as generally to discourage the Apostolic labourers for God, though it is certainly such as to cause great carefulness and fear among those who have the opportunity of listening to the Word of God.

For even though the number is not to be so very great of those who hear the Word of God altogether in vain, still there are all the dangers to be escaped of which our Lord speaks under the various images of the wayside, the shallow soil, and the ground occupied by the thorns.

With this preface, we may now proceed to the explanation of the Parable of the Sower, as it is given to us in the three Evangelists.

In the next piece, Fr. Coleridge will tell us…

How the wayside soil represents those whose hearts are hardened against the Word of God.

That Satan actively seeks to snatch away the seed, using distractions, passions, and worldly concerns.

Why even small disturbances in prayer or preaching may be the subtle workings of the enemy.

… and he will show us that vigilance and recollection are necessary to receive and retain divine truth.

Hit SUBSCRIBE now to make sure you don’t miss any future parts:

The Parable of the Sower

Part I: How does the Parable of the Sower unlock all Christ's other parables?

Part II: How do the birds reveal a brutal war for the soul in the Parable of the Sower?

Part III: What if your faith is shallow, and you won’t know until it’s too late?

Part IV: What makes for good soil in Christ’s Parable of the Sower?

Here’s why you should subscribe to The Father Coleridge Reader and share with others:

Fr Coleridge provides solid explanations of the entirety of the Gospel

His work is full of doctrine and piety, and is highly credible

He gives a clear trajectory of the life of Christ, its drama and all its stages—increasing our appreciation and admiration for the God-Man.

If more Catholics knew about works like Coleridge’s, then other works based on sentimentality and dubious private revelations would be much less attractive.

But sourcing and curating the texts, cleaning up scans, and editing them for online reading is a labour of love, and takes a lot of time.

Will you lend us a hand and hit subscribe?

Read next:

Follow our projects on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram: