The Sermon on the Mount—the New Law at the New Sinai

When Christ sat down on the Mount of the Beatitudes as the New Moses and Lawgiver, and he began to teach, who was actually around him—and what does this show us about his early ministry?

In the Roman Rite, the Gospel for the Mass of All Saints is that of the Beatitudes. Here is Father Henry James Coleridge’s account of the whole of the Sermon on the Mount, in preparation for that.

In this chapter, Fr Coleridge tells us…

Where the Sermon on the Mount fits into the beginning of Christ’s public life

What it shows us about the body of the disciples as it already existed

How it is related to the giving of the Old Law on Mount Sinai—and what this shows us about Christ as the new Lawgiver.

See also:

The Sermon on the Mount

From

The Preaching of the Beatitudes

Fr Henry James Coleridge, 1876, Ch. VIII, pp 123-136

St. Matt. v. 21; Story of the Gospels, § 31

A great monument of our Lord’s teaching

It has already been remarked that we have very few particular incidents preserved to us of the many months of extreme and varied activity which our Blessed Lord spent in the circuits of Galilee which are spoken of by the Evangelists.

This dearth of distinct anecdotes, miracles, acts of authority over the devils, and the like, is amply compensated for by the abundant treasures of holy doctrine which have been preserved for us in that great monument of our Lord’s teaching which is known as the Sermon on the Mount.

It was certainly most natural that the attention of the Apostles should be particularly directed to the records of our Lord’s teaching, which would come second only in importance to those acts of His in which the great mysteries of our salvation were wrought, and especially His Passion, and that, whenever a written Gospel came to be formed under their auspices and by one of themselves, it should be, in a very large measure, devoted to the preservation of that teaching.

Such a Gospel we have, as has elsewhere been shown, in the Gospel of St. Matthew, and the manner in which this Evangelist hurries on in his story to the great collection of doctrine which is embodied in the Sermon on the Mount can hardly fail to strike any careful student of the New Testament.

Importance of it in St Matthew’s Gospel—unparalleled in the others

St. Matthew seems to relate nothing before it except what was absolutely necessary, and he postpones to it those incidents of the Sabbath at Capharnaum which he selects later on in his Gospel, when he comes to weave, as it seems, a chain of our Lord’s miracles as specimens of His doings in that kind, incidents which nevertheless seem undoubtedly to have taken place at the very outset of our Lord’s public preaching in Galilee, and of which the Evangelist may have been an eye-witness.

Again, he contents himself, as we have seen, with the shortest possible description of our Lord’s course of preaching, simply enumerating the wide circle of provinces to which the influence of that preaching reached, and then he dwells with loving fulness upon the Sermon on the Mount, which forms no inconsiderable part of his whole work, and is, we may venture to say, a record of our Lord’s teaching perfectly unique in the whole New Testament.

The other Evangelists have added little of the same kind to these chapters of St. Matthew. St. Mark’s object is to dwell on our Lord’s wonderful displays of divine power, rather than on His direct teaching. St. Luke, always, like St. Paul, unwilling to ‘build on another man’s foundation,’1 has marvellously contrived to give a complete Gospel, at the same time that he avoids, as far as is possible, the repetition of what others had said before him, for which he usually substitutes something similar.

Thus he has given the far shorter Sermon on the Plain instead of this discourse recorded by St. Matthew. And the great mass of our Lord’s teaching2 which occurs in the central portion of St. Luke’s Gospel, and which is peculiar to him, might be more fitly compared to the later teaching of our Lord in St. Matthew, where the Evangelist collects so much which relates to what are called the counsels of perfection, than to the Sermon on the Mount.

The very large additions, on the other hand, to the remains of our Lord’s teaching, which make up the greater part of the Gospel of St. John, are chiefly disputations, a class of discourses almost entirely passed over by St. Matthew and the other Evangelists, or again, the outpouring of our Lord’s most tender confidence to His intimate friends at the Last Supper.

We are thus justified in considering the Sermon on the Mount as a document which has hardly any parallel in the rest of the Gospel records, as it is certainly a document which, more than any other, has furnished the principles of the moral teaching of the Christian Church in all ages.

The multitudes

St. Matthew introduces the Sermon on the Mount in direct connection with the multitude which followed our Lord, not only from Galilee, but from all the provinces of Palestine except Samaria.

We may gather from this, what indeed might be considered evident enough from the substance of the Sermon itself—that it was delivered after the preaching of our Lord had been continued for some time, and His fame and influence carried far and wide. The course of a great preacher who goes about from town to town, marking his footsteps by works of wonder and beneficence, is like the onward flow of a mighty river, which swells in volume as it proceeds through the plain, gathering into itself the streams which drain the valleys which it passes in succession.

Some of our Lord’s hearers would follow Him for a time, and their place would be filled by others, but the multitude would gradually swell as He passed from place to place. This multitude would be in the main composed of persons to whom His teaching was becoming familiar, and who were being gradually raised thereby higher and higher in spiritual discernment and cultivation. The formation of something like a large body of such persons would be a great step towards the foundation of the Church. It would be the providing of the flock of which the Apostles were to be the first shepherds.

Such persons would be like the good soil of which our Lord was afterwards to speak in the earliest of His parables, in which the seed was to be fruitful thirty fold, or sixty fold, or a hundred fold. They may not, of course, have been as disciplined and as organized a body as the bands of which we read as following St. Vincent, but they may still have differed very greatly from a promiscuous multitude in the ordinary sense of the term.

Different grades of believers

It may also be remarked that the time was not yet come when it would be necessary or prudent for our Lord to wrap up His teaching in parables, which could only be understood by the intelligent, without becoming an occasion of spiritual injury to the ill-disposed, captious, or obstinate hearers. And if there were any such among the multitudes who would flock to our Lord’s teaching out of curiosity in the towns, they would not be likely to put themselves to the trouble and inconvenience of following Him from spot to spot.

Thus that sifting of His audience, if we may so speak, which our Lord afterwards practised when He came to teach in parables, would be attained in a different way if our Lord so arranged the places and occasions of His teaching as to leave behind Him the crowd of the less advanced hearers, to whom what St. Paul afterwards called ‘the word of the beginning of Christ,’3 was more fitly to be addressed, and gather round Him the other multitude of followers who had already been taught ‘the foundation of penance from dead works, and of faith towards God,’ and so might be led on to ‘things more perfect.’

That our Lord did actually proceed in this way on the occasion of the Sermon on the Mount, seems to be implied by St. Matthew’s language—‘And seeing the multitudes, He went up into the mountain, and when He was sat down, His disciples came to Him.’

There would be no security against an utterly promiscuous multitude in the cities and towns, but when He withdrew to a comparatively lonely spot, He would still be followed by a crowd, but a crowd more or less composed of persons who were already His disciples.

Brevity of the sayings in the Sermon

When we come to examine closely the substance of the Sermon on the Mount in itself, we are at once struck with the preparation which it seems to require in the audience which was to receive it.

This will be more naturally drawn out further on. But it may be well to dwell here on another remarkable characteristic of this Sermon. It is a wonderfully close and compact body of doctrine, and, if it were merely recited or delivered as it lies before us in the volume of the New Testament, it would occupy a comparatively short time in such delivery.

The most important and pregnant maxims and precepts are here set forth with the utmost brevity. The Sermon is in truth a perfect code and system of perfection. The Beatitudes and the Lord’s Prayer, to speak of nothing else, contain a number of heads of doctrine which can only be developed by long meditation and explanation.

We have certainly no right to say that our Lord could not, if it had so seemed good to Him, have put forward these precepts and maxims of heavenly wisdom in the short and almost proverbial form in which we now read them in the pages of St. Matthew; or that, if it had pleased Him, He might not have passed so rapidly from one subject to another, and compressed so many various heads of the most momentous doctrine into so short a time as would be required if we were to understand the Sermon, as a whole, to have contained nothing but what has been preserved to us.

But the delivery of such a compact summary of doctrine in such a form in the course of ordinary teaching would seem at first sight improbable, and unlike our Lord’s usual method of teaching, as far as we can gather it from the Gospels. It would certainly also be unlike the traditional manner of teaching in the Church, in which we are most familiar with the more gradual modes of instruction.

The parables of our Lord, for instance, are usually devoted to the setting forth of one truth at a time concerning the method of God’s government of the world, and the more didactic portions of the discourses in St. John’s Gospel do not pass with great rapidity from one subject to another.

Nor, indeed, as to any of our Lord’s recorded discourses, whether private conversations such as those with Nicodemus or the Samaritan woman, or disputations such as those with the Jews at Jerusalem after the miracle on the Sabbath day, or that in the synagogue at Capharnaum after the multiplication of the loaves, and others like them, or again, such as the long discourse with the eleven Apostles after the Last Supper, can we be certain that we have more recorded for us than the chief heads of the conversation, or argument, or discourse.

The Sermon has a character of its own

We are therefore left somewhat to conjecture, both in general as to the discourses of our Lord in the Gospels, and in particular as to the Sermon on the Mount, not indeed as to the perfect faithfulness of the report which remains to us, but as to its being a literal and exact record, word for word, of all that fell from our Lord. Nor is it forbidden us to suppose that He added explanations and developments of the doctrines which are summed up in the sentences of His Sermon, which developments have been omitted.

Perhaps, however, when the occasion on which the Sermon on the Mount was delivered is considered, and its due importance in the series of the manifestations of our Lord is taken into account, it may seem more natural to think that it is not an ordinary discourse or instruction, one out of many which has here been preserved to us, by way of specimen, by St. Matthew.

We may come to think that it had a character and authority of its own, as indeed might naturally be inferred from the unusual and very solemn circumstances of its delivery. It could not have been merely for convenience that our Lord ‘went up into the mountain’ on this occasion, as on one or two others, when He was about to take some very great step in the fulfilment of His mission, such as the appointment of the Apostles or the manifestation of the glory of His Sacred Humanity in the Transfiguration.

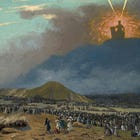

The delivery of this Sermon is an occasion of this kind, and we may thus arrive at a more accurate understanding of its authority as a kind of Code of the New Covenant, answering in many respects to the Law which was delivered on Mount Sinai in the Old Covenant. Many beautiful thoughts on this subject are to be found in the old Catholic writers, and it may perhaps be our best wisdom to look on them, not only as pious contemplations, but as resting on solid truths relating to the dispensation of the Incarnation, the office and mission of our Lord, and the manner in which these were gradually fulfilled and, as it were, unfolded in His Public Life.

The rest of this article is for members of The Father Coleridge Reader.

Sourcing and curating the texts, cleaning up scans, and editing them for online reading is a labour of love, and takes a lot of time.

If you value what we’re doing at The Father Coleridge Reader, will you give us a hand and keep the project alive?