Why did Christ invite himself to the house of the hated Zacchæus?

After healing the blind beggars, Jesus dined at the house of a rich sinner on his way to the Cross.

After healing the blind beggars, Jesus dined at the house of a rich sinner on his way to the Cross.

Editor’s Notes

In this piece, Fr. Coleridge tells us…

How Zacchæus’ encounter with Christ led to his complete conversion.

That Christ’s mercy transcends human prejudice, bringing salvation even to public sinners.

Why Christ invited Himself, showing His initiative in seeking the lost.

He shows us that true repentance requires both contrition and restitution.

Christ’s encounter with Zacchaæus comes on his final journey to Jerusalem and the Cross. It comes just after he foretold his Passion to his Apostles, and healed the blind near Jericho. Jericho itself was a wealthy and populous city near the Jordan, where Zacchæus was the chief publican.

These incidents show that:

Christ heals both physical and spiritual blindness

On his way to the Cross, Christ bestows his blessings on both the poor beggars and the rich tax collector

In both cases, Christ is rewarding the persistence of those seeking him.

Zacchæus conversion manifests the purpose of Christ’s coming: “The Son of Man is come to seek and to save that which was lost.” His repentance and restitution illustrate how salvation is found in responding to grace.

Our Lord at Jericho

The Preaching of the Cross, Vol. III

Chapter XIII

St. Matt. xx. 29–34; St. Mark x. 46–52; St. Luke xviii. 35–43, xix. 1;

Story of the Gospels, § 129

Burns and Oates, London, 1888

Headings and some line breaks added.

Immediately after the passage sung on Quinquagesima Sunday

Part I: What does Blind Bartimæus show us about calling upon Christ with faith?

Part II: Do the Gospels contradict each other about Blind Bartimæus?

Part III: Why did Christ invite Himself to the house of the hated Zacchæus?

Zacchæus

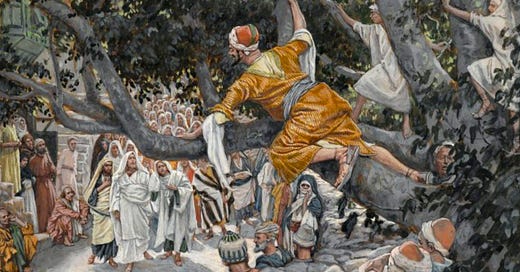

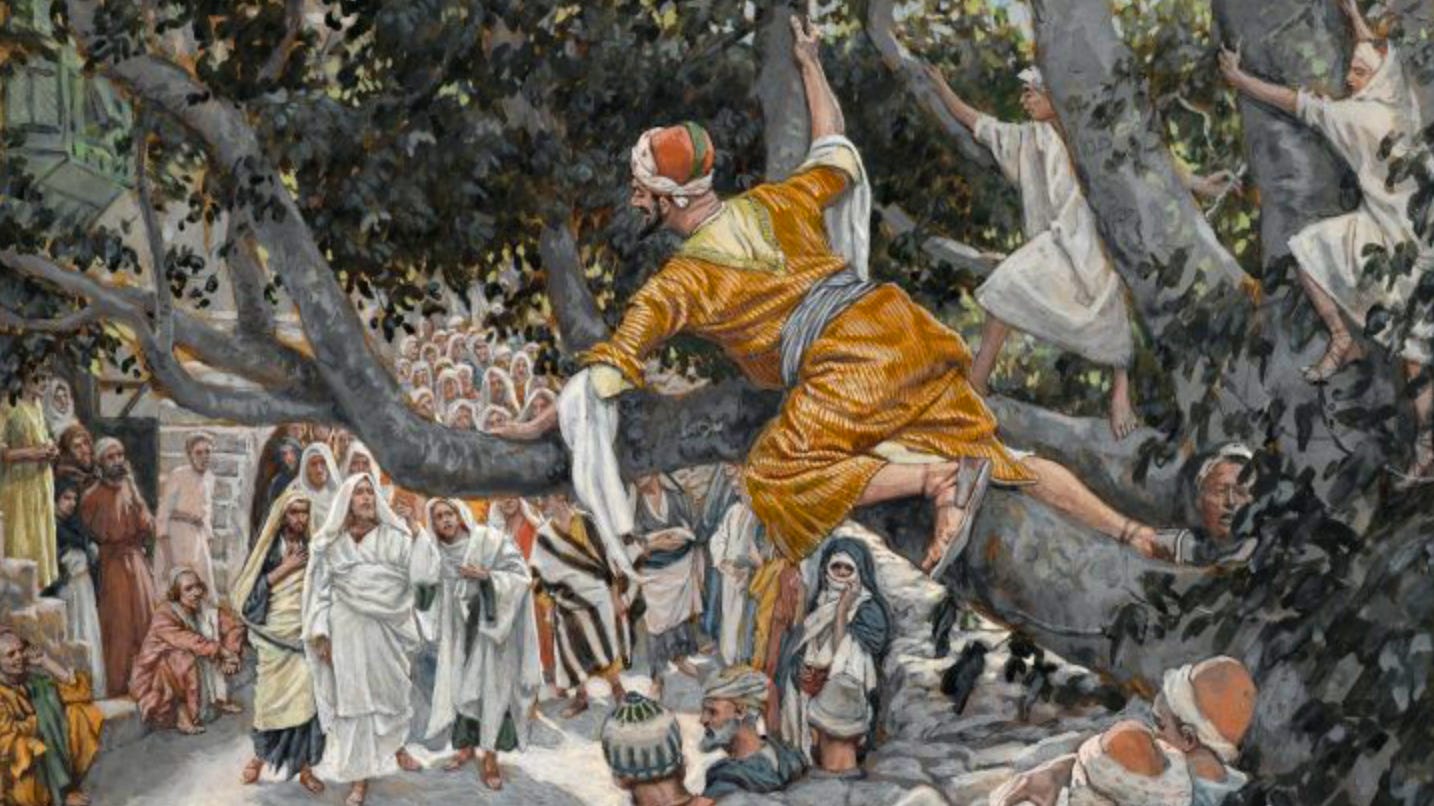

‘And behold there was a man named Zacchæus, who was the chief of the publicans, and he was rich. And he sought to see Jesus, Who He was, and he could not for the crowd, because he was low of stature. And running before he climbed up into a sycamore-tree, that he might see Him, for He was to pass that way.’

Zacchæus was a resident in the neighbourhood of Jericho, possibly at some distance along the road. Our Lord had His own plans with regard to him, and perhaps it entered into them, not only to bring about his perfect conversion, but to use his house as a resting-place for the night, that He might without any ostentation or pomp finish His journey in Jerusalem apart from the crowd, and spend the evening before the Day of Palms with His dear friends at Bethany.

Zacchæus was in waiting at some spot on the road, but he soon found that he could not satisfy his curiosity about our Lord, on account of the crowd by which He was surrounded, and his own low stature. So he ran on, and climbed the tree, which must have been by the roadside, that he might see Him pass. Curiosity was his main motive, but he was uneasy in his conscience, and he felt instinctively that our Lord could give him peace. Thus his curiosity was an instrument that his conscience used to bring him across our Lord.

Our Lord at his house

‘And when Jesus was come to the place, looking up, He saw him and said to him, Zacchæus, make haste and come down, for this day I must abide in thy house. And he made haste, and came down, and received Him with joy.’

We do not know that our Lord was in the habit of inviting Himself, but He could do this, and even into the house of a publican, for the sake of helping a soul to salvation, as He could stop on His march to listen to the call of the poor blind men whom He had lately healed. In this case there was some offence given to the multitude of pilgrims.

‘And when all saw it, they murmured, saying, that He was gone to be a guest with a man that was a sinner.’

This is what St. Luke makes the prominent feature in the story, for the reason that the sequel was to show that the ‘man that was a sinner’ was converted entirely from his sin. The publicans were unpopular, not only from the extortions which many of them, no doubt, exercised, but also because they were the representatives of the ‘alien’ government to which the dues were paid which they farmed from that government.

There was a hatred against that government in the Jewish mind, which was highly national, although they lived under its laws in peace and security, and enjoyed many privileges which they had not known under other masters. For the Roman yoke was mild in many respects, and it was particularly considerate in the case of the Jews with respect to their religion. In the time of which we speak, the people were probably more secure as to personal liberty and as to the administration of justice than they had been under Herod, and in the dark times which were to succeed after our Lord’s Crucifixion the great protection to His Church was, as has been said, in the Roman power.

Our Lord had no scruple whatever in offending the national prejudices against the publicans, and it is remarkable that He should have done this on so public an occasion and so near before His Passion.

The rest of this article is for our monthly/annual supporters. The Father Coleridge Reader is a labour of love.

But curating, cleaning up and publishing these texts takes a lot of time—and we like to give a little back to those who support the project.

Please consider joining to keep this project going!