Do the Gospels contradict each other about Blind Bartimæus?

St Matthew's Gospel includes a similar miracle to the healing of Blind Bartimæus, but with different details. Is this a contradiction, or something else—and how can we know?

St Matthew's Gospel includes a similar miracle to the healing of Blind Bartimæus with different details. Is this a contradiction, or something else—and how can we know?

Editor’s Notes

In this piece, Fr. Coleridge tells us…

How St. Matthew summarises miracles while preserving their essential meaning.

That Christ’s condescension in healing the blind teaches perseverance in prayer.

Why the Evangelists' varied accounts reveal divine providence in Scripture.

He shows us that charity means setting aside our own urgency, so as to serve others with Christ-like attention.

This healing of “Blind Bartimæus” and the other two blind men takes place during Our Lord’s final journey to Jerusalem for his Passion, and just after his raising of Lazarus.

Our Lord at Jericho

The Preaching of the Cross, Vol. III

Chapter XIII

St. Matt. xx. 29–34; St. Mark x. 46–52; St. Luke xviii. 35–43, xix. 1;

Story of the Gospels, § 129

Burns and Oates, London, 1888

Headings and some line breaks added.

Sung on Quinquagesima Sunday

Part I: What does Blind Bartimæus show us about calling upon Christ with faith?

Part II: Do the Gospels contradict each other about Blind Bartimæus?

Part III: Why did Christ invite Himself to the house of the hated Zacchæus?

These miracles in St Matthew’s Gospel

It is St. Matthew’s way to be summary, concise, and to use the plural number where he can. But it would be an unreasonable conclusion to form, that he uses it when it cannot truly be used. He uses it in the case of the legion of devils, and of the thieves on the cross reviling our Lord, when the more detailed narratives mention only one demoniac, and one thief as reviling.

St. Mark and St. Luke have a special reason for this, which need not be explained here. We have here related two miracles on the blind, the one, as St. Luke tells us, before the entrance into Jericho, the other, as St. Mark tells us, after the exit from that city, in which our Lord did not stop, but walked through it. St. Matthew tells us,

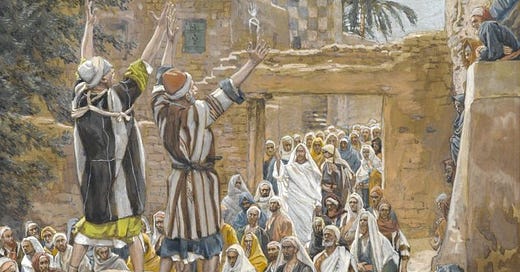

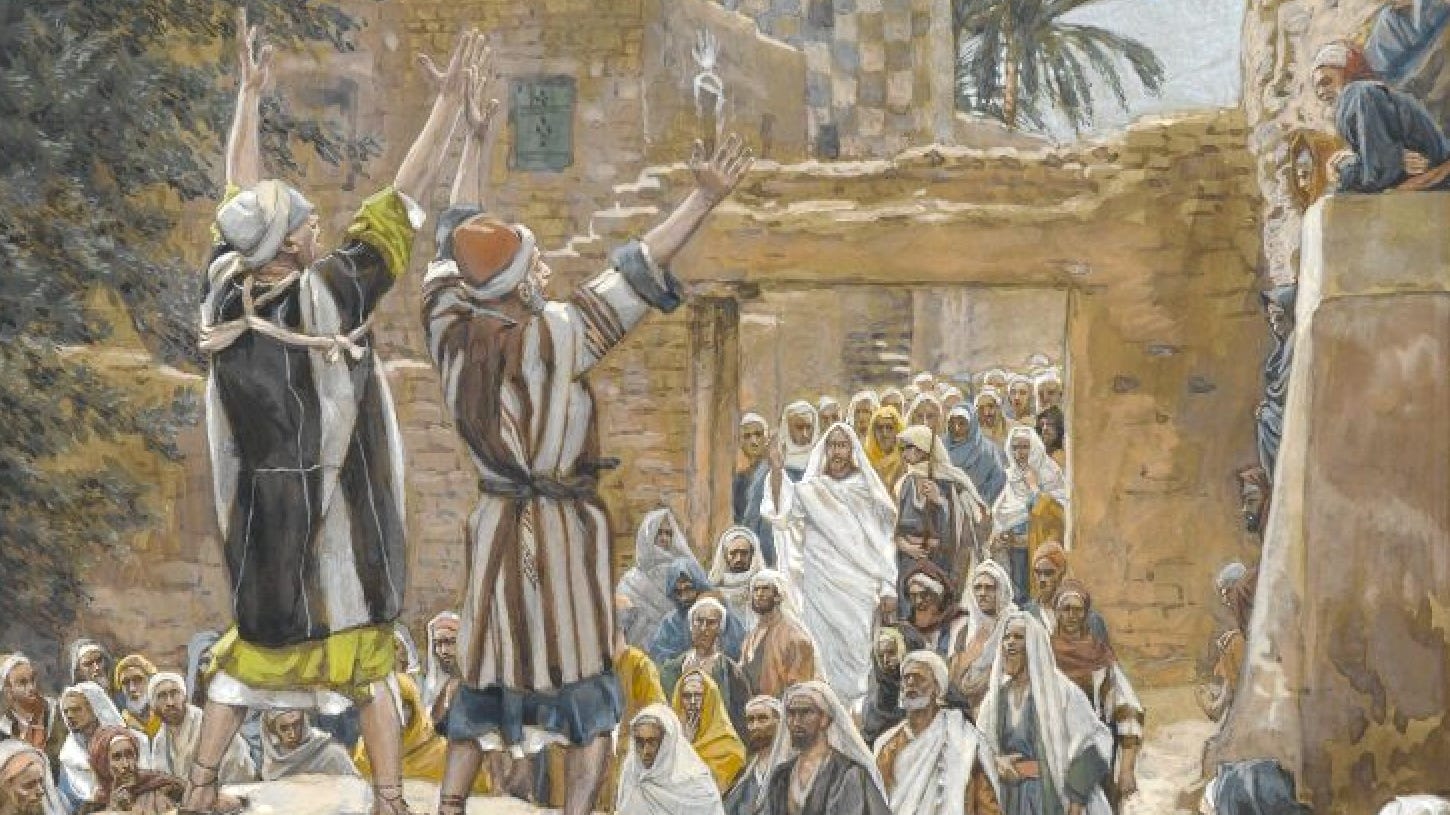

‘Behold, two blind men sitting by the wayside, heard that Jesus passed by, and they cried out, saying, O Lord, Thou Son of David, have mercy on us! And the multitude rebuked them, that they should hold their peace. But they cried out the more, saying, O Lord, Thou Son of David, have mercy upon us! And Jesus stood, and called them, and said, What will you that I do to you? They say unto Him, Lord, that our eyes be opened. And Jesus, having compassion on them, touched their eyes. And immediately they saw, and followed Him.’

St. Matthew thus groups the two cures together, and in doing this, he appears, of set purpose, to have omitted whatever is peculiar to the one case or the other, and to have related what was common to both. He gives no name, though he must have known Bartimæus as well as St. Mark. He omits the words to one of the blind men, ‘Be of better comfort, He calleth thee,’ and the incident of his casting away his outer garment, and leaping up. He omits our Lord’s words after the cure, which may have been a little different in each of the two cases. He mentions what is not mentioned by the other Evangelists, that He touched their eyes.

His narrative is perfectly accurate, while at the same time he describes the miracles without saying that they were performed at different times and spots. That is all that can be fairly said against his accuracy, but in a case like this, it was not necessary, nor even opportune, to relate the miraculous cures each separately. The point of the narrative is perfect in each, namely, the affability and humility of our Lord in working the miracle at the prayer of the blind, which was made in a manner and at a time which, at all events, seemed to the companions of our Lord inopportune and inconvenient.

For this circumstance also is almost peculiar to these miracles among those which are recorded, namely, that the petitioners were rebuked by others, just as the parents of the children who were brought to our Lord were rebuked by the Apostles, with whom our Lord was therefore displeased.

An apparent difficult

There is one apparent difficulty about St. Matthew’s narrative, which may be explained in a few words. He prefixes to his account of the miracle, the words, ‘And when they went out from Jericho, a great multitude followed Him. And behold two blind men sitting by the wayside,’ and the rest. That is, he seems to place the miracles of which he speaks after the exit from Jericho. It is perfectly true, that according to the explanation here given, one of the two was healed before the entrance into Jericho, and the other, the most famous of the two, after the exit from the city.

But it requires little acquaintance with St. Matthew’s style to see that the difficulty is only apparent. A great number of the seeming difficulties as to the order in St. Matthew come from the mistaken opinion that he intends us to think that when he puts one thing next to another he means that it followed upon that other, even when he begins the second narrative with words like ‘and behold.’

It would be quite as true to say that he means those words to disjoin what follows from what precedes, as that he means them necessarily to imply connection. What St. Matthew really says is that great multitudes followed our Lord as He went out of Jericho, a statement which would be true of His approach to that city, but much more so of His departure, and also when he relates, in his own way, the double miracle, without intending to specify whether it occurred after or before the passage through Jericho.

This is the explanation which seems certainly true. But it may also be added that St. Matthew, having determined to conjoin the two similar miracles, and mention what was common to them, might have felt free to place his narrative either before or after the passage. But, as has been said, he seems not to have meant in any way to connect the miracle with the passage through Jericho.

Textual Note I: St Matthew’s ordering of events

An exactly parallel case is to be found at the beginning of the ninth chapter of this Gospel. ‘And entering into a boat, He passed over the water, and came into His own city. And behold, they brought Him one sick of the palsy, lying on a bed.’ It is as certain as anything of the kind can be, that these sentences relate to events which occurred at a wide interval, and that the last incident, the cure of the paralytic, took place before the other.

Our Lord’s passage of the water was after the miracle on the legion of devils, when the people of the country besought Him to ‘depart from their coasts.’ The cure of the paralytic took place before the call of St. Matthew, and before the second Pasch. It was, in fact, one of the earliest of the recorded miracles (See Story of the Gospels, § 39). St. Matthew, as has been said more than once, in his eighth and ninth chapter, collects a number of miracles together, without regard to the dates at which they were performed, to show our Lord’s power in various ways, over leprosy and other diseases, and the powers of nature, and the devils. The words καὶ ἰδοὺ are his common way of beginning a new subject. Instances of this might be found in almost every chapter, and it is not peculiar to St. Matthew.

It may be added that it may seem to some critics that we are here explaining a difficulty in St. Matthew, and that the explanation solves an objection we have used against doing apparent violence to the order in St. Luke. For St. Luke, after his account of this miracle, says, ‘And entering in, He passed through Jericho. And behold there was a man named Zacchæus,’ &c., and he proceeds to speak of his conversion. It may be said, why should not the passing through Jericho belong to the incident of Zacchæus, which certainly followed it, and not to the healing of the blind man, which is said to have preceded it?

The answer is two-fold. St. Luke is in general a great deal more observant of the strict order of events than is St. Matthew. But besides this, he has prefixed to his account of the miracle words which fix its time and place. ‘And it came to pass, when He drew nigh to Jericho,’ that is, as He was drawing nigh to Jericho, ‘a certain blind man sat by the wayside begging.’

The lesson of the miracle

We have had to dwell somewhat at length on a critical difficulty, and we must not leave out of sight the beautiful lesson which we are able to gather from the manner in which the three narratives taken together illustrate the character of our Lord. We learn from them it was not once only, but twice over, that He stopped on His march to listen to the same prayer from a petitioner with the same needs.

Often indeed are His servants inclined, and almost forced, to disregard inopportune applications, whether for material or for spiritual alms, and they are wont to plead excessive occupations and business of higher importance as a reason for setting aside troublesome claims on their time. It must often be so, for the time of the ministers and servants of our Lord is very short, and the applicants may be many. But it would be well if His example were always before us, as a help against the temptation to let fatigue or excess of business ruffle our peace, and make us inattentive to what may perhaps be the task which He sets us, here and now.

Our Lord always found time for what He had to do, and attended to all. His saints have ways of their own, caught from Him, of attending to an almost infinite number of matters with perfect tranquillity and quiet swiftness, because they attend to each matter as it comes before them as if it were the only matter which it behoves them to care about at the time. In the midst of this almost solemn triumphal march, He was the servant of one blind man after another, and gave Himself to them with immense calmness and sweetness.

He is the same in hearing our prayers. How many times over do we go to Him for the same boon, nay, for pardon for the same faults and disloyalties? Yet it is always the same—‘What wilt thou that I do to thee?’ And we shall have greater power over His Sacred Heart for our own prayers, if we give ourselves, in the same patient spirit, to the service of our neighbour.

Textual Note II—How the Evangelists wrote

It may be added here to what has been said about the narratives of the three Evangelists, which we believe to be certainly accurate in themselves and to be easily taken in conjunction, as has been done in the text, that they seem each to have done in this matter what is most characteristic of them. St. Matthew gives the miracles conjoined, in a succinct manner, but without omitting a single point which was important.

St. Mark comes after him, and adds the details in full about Bartimæus, leaving unexplained—as he does in the case of the legion of devils—his omission of the plural number. He also brings out the point of the miracle he relates, which is common to both. Thus he has done what was necessary, at the same time that he tacitly implies that not both the men mentioned by St. Matthew were healed after the passage.

Then comes St. Luke, and in his almost invariable manner, he adds what St. Mark has left out, and shows that there were two men healed, as St. Matthew had stated. It would have been superfluous for either of the two later Evangelists to tell the full story, for then many details would have had to be repeated twice over in the same context. This the Evangelists would not be likely to do. Thus there is something left by them for their students to draw from the apparent difficulty which has here been dealt with.

It must always be remembered that God the Holy Ghost is the Author of Scripture, as a whole, as well as of every part of it, and His Divine authorship has certainly to be taken into account in the disposition of its parts and the arrangement of its several books. This is necessarily in this respect more conspicuous in the four Gospels than elsewhere, because in them the same Divine history has to be told by four different authors, certain features thereof being allotted specially to each one of the four.

Fervour of the multitude

These miracles on the blind men must have raised the hearts of the disciples and the multitude to a state of enthusiasm. It was not merely that our Lord had shown His Divine power, as He had so often shown it before. He had condescended to the prayer of these urgent suppliants, and thus shown great humility and mercifulness.

There was no elation in His behaviour at this juncture, when, as we shall see from the account of what passed on the Day of Palms, which was immediately to follow, the great multitude of His disciples had been collected for the first time since the resurrection of Lazarus, and were full of triumph and of lofty expectations. The company must have passed on joyously and full of hope. The distance from Jericho to Jerusalem was not too great to be accomplished within the day, and if the passage through Jericho had been in the course of the morning, the pilgrims might press on, and reach the neighbourhood of the Holy City before nightfall.

A great number of them, probably, looked to finding some shelter in the neighbourhood of the city, rather than in Jerusalem itself. A fresh incident, however, was to occur, showing again our Lord’s extreme condescension, and which perhaps separated the great multitude of His followers from His own immediate companions, so that they did not all approach Jerusalem together.

Our Lord at Jericho

Part I: What does Blind Bartimæus show us about calling upon Christ with faith?

Part II: Do the Gospels contradict each other about Blind Bartimæus?

Part III: Why did Christ invite Himself to the house of the hated Zacchæus?

Here’s why you should subscribe to The Father Coleridge Reader and share with others:

Fr Coleridge provides solid explanations of the entirety of the Gospel

His work is full of doctrine and piety, and is highly credible

He gives a clear trajectory of the life of Christ, its drama and all its stages—increasing our appreciation and admiration for the God-Man.

If more Catholics knew about works like Coleridge’s, then other works based on sentimentality and dubious private revelations would be much less attractive.

But sourcing and curating the texts, cleaning up scans, and editing them for online reading is a labour of love, and takes a lot of time.

Will you lend us a hand and hit subscribe?

Read next:

Follow our projects on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram: