What does Blind Bartimæus show us about calling upon Christ with faith?

The blind man’s persistence and Christ’s merciful response highlight the necessity of faith and perseverance in prayer.

The blind man’s persistence and Christ’s merciful response highlight the necessity of faith and perseverance in prayer.

Editor’s Notes

In this piece, Fr. Coleridge tells us…

How Christ's final journey to Jerusalem set the stage for His Passion.

That the multitudes surrounding Him reflected both devotion and expectation.

Why the healing of the blind at Jericho reveals Christ’s condescension and power.

He shows us that perseverance in prayer, despite obstacles, draws divine mercy.

This healing of “Blind Bartimæus” and the other two blind men takes place during Our Lord’s final journey to Jerusalem for his Passion, and just after his raising of Lazarus.

Our Lord at Jericho

The Preaching of the Cross, Vol. III

Chapter XIII

St. Matt. xx. 29–34; St. Mark x. 46–52; St. Luke xviii. 35–43, xix. 1;

Story of the Gospels, § 129

Burns and Oates, London, 1888

Headings and some line breaks added.

Sung on Quinquagesima Sunday

Part I: What does Blind Bartimæus show us about calling upon Christ with faith?

Part II: Do the Gospels contradict each other about Blind Bartimæus?

Part III: Why did Christ invite Himself to the house of the hated Zacchæus?

Our Lord approaching Jericho

Shortly before the incidents lately mentioned, our Lord appears to have begun His last journey to Jerusalem, a journey which was to lead Him to His Passion. The last distinct note of place before those incidents, according to the order which is here followed, is the mention of the ‘city called Ephrem,’ to which our Lord retired after the miracle on Lazarus.

St. John describes the place as a country near the desert, or less populated region on either side of the Jordan, and it seems to have been on the further side of that river. From thence, as soon as the time for the Pasch drew nigh, our Lord would move once more towards the Jordan, and cross the river at the usual ford, from which the road ran straight through Jericho towards Jerusalem.

On the way thither we are told that He again predicted His Passion with greater detail than ever before. It was on this journey also that He pressed onwards before them with so much earnestness as to excite their wonder, and that He received and answered the petition of the sons of Zebedee, made through their mother Salome, as has been considered in the last chapter. In the neighbourhood of Jericho, which He now was visiting for the last time, some remarkable things occurred of which we are now to trace the narrative.

Great multitudes

We must remember that our Lord was likely to have constantly a large following in any part of the country where He showed Himself and taught, and on this occasion there must have been also a certain number of persons who were more or less His disciples, and who would naturally go to Jerusalem at the same time and for the same purpose as Himself.

It was perhaps not more than two days’ journey to Jericho. Our Lord would thus approach the city with a large multitude in attendance on Him. The effect of His preaching and His miracles was undoubtedly very great, though we are constantly in danger of forgetting it, on account of the great silence of the Evangelists. Before reaching Jericho the multitude would probably be increased largely by other multitudes of pilgrims from Galilee, who ordinarily crossed the Jordan at the bottom of the Lake of Tiberias, and again opposite Jericho, in order to avoid the passage through Samaria.

There might also very likely be others waiting for our Lord’s approach, and in any case, as it was apparently the last stage on the road to Jerusalem, the caravan, so to speak, would be more and more thronged as it went on. It was at all times an occasion of much fervour, each band of pilgrims adding, not only to the numbers, but to the enthusiasm of the rest.

There is much of blessed contagion about devotion, which is greatly intensified and spread by the companionship of a multitude, united with ourselves in the same happy feeling of confidence in God. This is the natural effect of great ‘functions,’ as we call them, and pilgrimages, and occasions of like character, which often have an immense effect on the soul. There is a special blessing on worship and devotion practised in common with others, which the envious jealousy of the indevout sometimes sneers at, and, when in power, endeavours to suppress by not allowing its occasions. It is astonishing how keen is the instinct of the enemies of the Church in suppressing everything of the kind.

These multitudes were gathered together for the ordinary purpose of the annual visit to Jerusalem at the feast, which, among other effects, seems to have had that of keeping alive the national feeling among the Jews. At this time, however, there must have been a special enthusiasm among numbers of the pilgrims, from the great fame of our Lord and the wonderful veneration for Him which had been quickened by the miracle on Lazarus. If the renown of this had not spread in Galilee, the Galileans would hear of it from the other pilgrims, and there would naturally be not only devotion to Him in consequence, but a general expectation of some great manifestation at the approaching feast.

Crowds to see them pass

We must, therefore, suppose that this was a great occasion, that the multitudes were unusually large, and that a great crowd would be collected also to see them pass. It is natural that such crowds should be greatest at the entrance into and the exit from the city. Such places would be the favourite spots where the mendicants and objects of compassion would place themselves. The streets of the Eastern cities were ordinarily very narrow, and the beggars would collect at the gates as they do at the doors of the churches at great festivals, or at the Quarant’ Ore.

It may also be remarked that it would not be a convenient time for teaching or for miracles, nor is it very likely that ordinarily sick persons would be brought to our Lord in large numbers, as He would only pass on His road. But the blind and the lame, and such as were otherwise able-bodied, would gather in considerable numbers, chiefly for the purpose of begging alms of the pilgrims, but in the case of those who had faith, of seeking some miraculous cure.

Cures of the blind

That the cures wrought on this occasion were remarkable in some way is evident from the care which has been taken by all three Evangelists to give an account of what happened. On a careful comparison of the three narratives, the feature which was remarkable can be discovered, and we have here an instance which shows the importance of such a careful comparison, while without it we can hardly meet the difficulty that can be urged against the story on the ground of carelessness or even some slight inaccuracy.

It need hardly be said that such inaccuracy ought never to be admitted, and still less in a case like this, where the Evangelists speak with extreme precision, and an obvious intention, in the very words in which the inaccuracy is supposed to lie. When a later Evangelist leaves out what another mentions, and inserts what the other omits, he ought naturally to be supposed to intend to supplement the other’s narrative. Unfortunately, too many critics are inclined to think that he means to contradict it, which is absurd, or that he is ignorant of what has been said before him, which is disrespectful.

The circumstances of the occasion have already been described. The first incident in the narration of the miracles may be given in the careful narrative of St. Luke, who here again, as is so frequently the case, adds to the history something more which has not been described by the other Evangelists (except in a word by St. Matthew), and is very similar indeed to what those others have described.

‘Now it came to pass, when He drew nigh to Jericho, that a certain man sat by the wayside begging.’

He had taken his post by the way along which the crowd passed, in order to gather alms.

‘And when he heard the multitude passing by, he asked what this meant. And they told him that Jesus of Nazareth was passing by. And he cried out, saying, Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me. And they that went before rebuked him, that he should hold his tongue, and he cried out much more, Son of David, have mercy upon me! And Jesus, standing…’

… that is, stopping on His march, notwithstanding the inconvenience, for the caravan was moving in the manner of a procession…

‘…commanded him to be brought to Him. And when he was come near, He asked him, saying, What wilt thou that I should do to thee? And he said, Lord, that I may see! And Jesus said to him, Receive thy sight, thy faith hath made thee whole. And immediately he saw, and followed Him, glorifying God. And all the people, when they saw it, gave praise to God. And entering in, He walked through Jericho.’

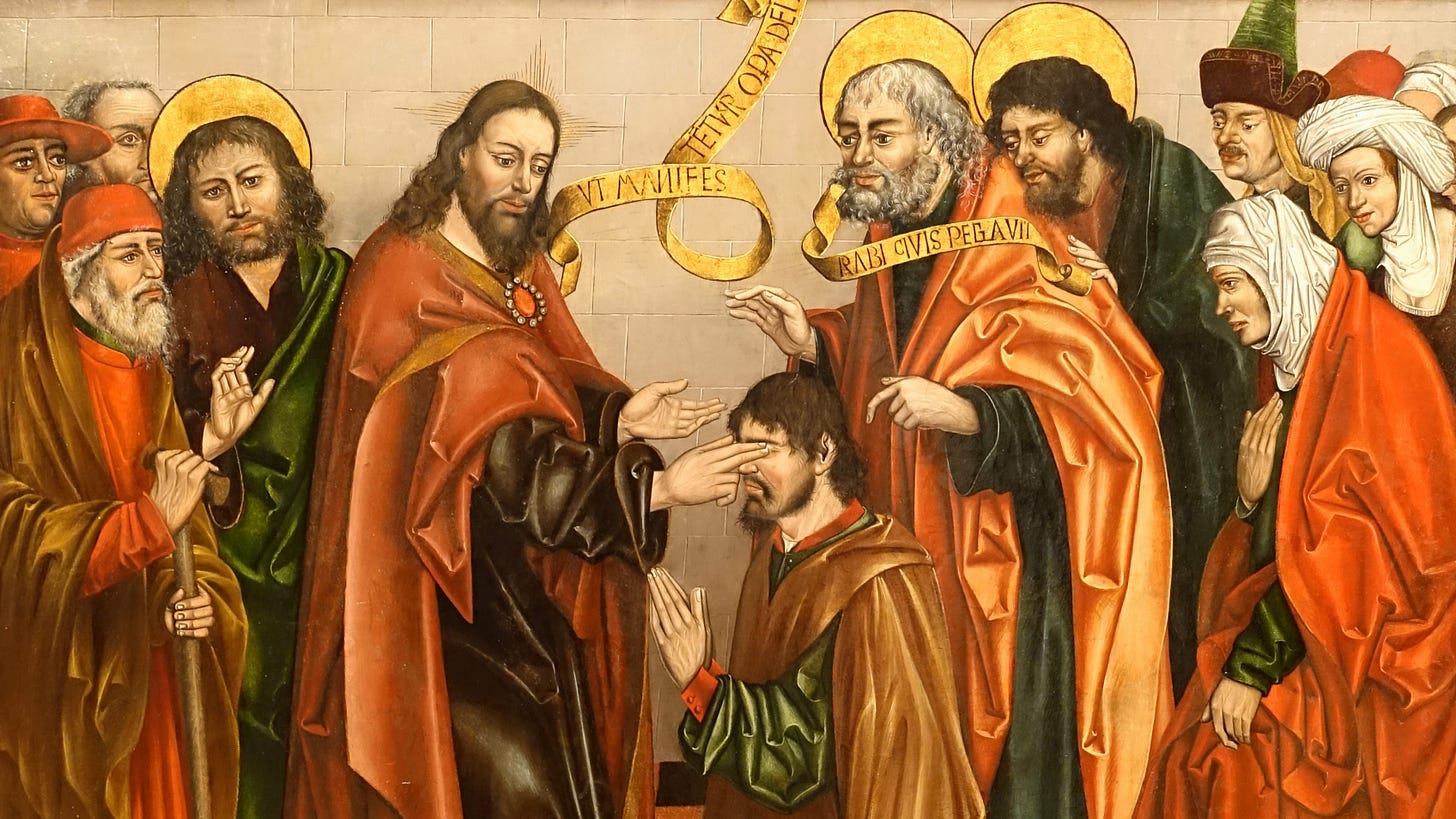

Its meaning

With regard to the miracle itself, we need say but little. It is perhaps merely an accident, but certainly the invocation of our Lord as the ‘Son of David’ is peculiar in the Gospels to the blind men mentioned in connection with Jericho here, and to the two blind men who were healed at Capharnaum just after the miracle on the daughter of Jairus.1

It was not the common way in which our Lord was addressed by those who sought His mercy. It is generally, Master, Rabbi, or something of the same sort. But it is clear that the feature on which the mind of the Evangelist is fixed is the extreme condescension and kindness of our Lord, Who would not let the cry of the blind man come to His ears in vain, and Who stopped the whole procession of His followers rather than let it go unheeded and unrewarded.

This man had faith, or he would not have called on our Lord as he did, and he had confidence also in the goodwill and tenderness of the great Teacher in continuing his prayer all the more importunately, notwithstanding the rebukes of those who went before, who may be supposed to have been charged with the care of keeping order and preserving the procession from interruption.

The miracle reads like a comment on the precept of ‘praying and not fainting,’ which our Lord had lately given; and His ready acquiescence in the prayer is a figure of the manner in which God will deal with those who know how to be holily importunate. The other incidents, such as the question of our Lord, ‘What wilt thou that I should do to thee?’ and His answer to the blind man, ‘Thy faith hath made thee whole,’ are common to this miracle and several others. The blind man follows Him, glorifying God, and the people give praise to God.

It is to be noted, moreover, that St. Luke, who begins the account of the miracle by saying that it was ‘when He drew nigh to Jericho,’ adds, at the end, in the most pointed manner, ‘And entering in, He walked through Jericho.’ It is not, therefore, that St. Luke has related the miracle, and without thinking of the circumstances, has placed it before the entry into Jericho instead of after. He has carefully warned his readers against mistaking him, and has twice over told us that it was before the entrance.

And in doing this he must have been quite aware that he was warning his readers against the supposition that he was relating the same miracle as St. Mark, who, with equal carefulness, as we shall see, tells us that our Lord cured a blind man on this occasion, but that it was after His departure from Jericho.

Miracle in St Mark

Let us now hear St. Mark. ‘And they came to Jericho, and as He went out of Jericho with His disciples, and a very great multitude, Bartimæus, the blind man, the son of Timæus, sat by the wayside, begging.’ He was probably a well-known man among the disciples, and is therefore named by the Evangelist.2

‘Who when he had heard that it was Jesus of Nazareth, began to cry out, and to say, Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me. And many rebuked him, that he should hold his peace, but he cried out a great deal the more, Son of David, have mercy on me. And Jesus standing still, commanded him to be brought. And they call the blind man, saying to him, Be of better comfort, arise, He calleth thee.’

These little details are characteristic of St. Mark, who may have had them from Bartimæus himself.

‘Who casting off his garment…’

… his outer garment that he might move more quickly…

‘… leaped up and came to Him. And Jesus answering, said to him, What wilt thou that I should do to thee? And the blind man said, Rabbi, that I may see. And Jesus saith to him, Go thy way, thy faith hath made thee whole. And immediately he saw, and followed Him in the way,’—not, St. Mark says, into the city.

The circumstances and words of this miracle are almost entirely the same with those of the former. But then it must be remembered that the occasion was almost identical, the need of the petitioner identical, and our Lord’s words were such as He commonly used when such a petition was made to Him. ‘What wilt thou?’ was His usual way, because it gave the person an occasion of showing his faith, and in like manner, ‘Thy faith hath made thee whole,’ was His usual way of dismissing the persons cured, partly out of humility, that He might attribute the cure to them, and partly because it was useful to show the power of faith in such cases.

There is, therefore, nothing more extraordinary in the identity of the circumstances than there is in the fact of the men having been both blind, both beggars, and both sitting by the way at a time when there were probably scores of such mendicants within half a mile of them. Many writers have an extreme reluctance to seem to multiply the miracles of the Gospel. But we have probably not a ten-thousandth part of the miracles of our Lord recorded, and there must have been a great sameness about their wonderful multiplicity. Our Lord ordinarily asked what was wanted, for the sake of the bystanders. He ordinarily granted what was asked, and commended their faith as the means of the cure.

The feature of these miracles which appears to have struck the minds of the Evangelists has been already named. That feature was the extreme condescension of our Lord in letting Himself be interrupted on a solemn occasion—for such was this procession of pilgrims—stopping on His road, and bidding the blind man be brought to Him. This is duly chronicled by both the Evangelists whom we have quoted. On the other hand, they add little touches which distinguish the several narratives.

If we had no more than St. Mark’s and St. Luke’s account, we should certainly think it most reasonable of itself, as well as most respectful to the accuracy of the Evangelists, to suppose that they do not contradict one another as to those words, evidently not inserted without a purpose, in which they seem to diverge. We may perhaps gain some clearer light from an examination of the account of St. Matthew, who, it will be remembered, certainly wrote before St. Mark and St. Luke.

Our Lord at Jericho

Part I: What does Blind Bartimæus show us about calling upon Christ with faith?

Part II: Do the Gospels contradict each other about Blind Bartimæus?

Part III: Why did Christ invite Himself to the house of the hated Zacchæus?

Here’s why you should subscribe to The Father Coleridge Reader and share with others:

Fr Coleridge provides solid explanations of the entirety of the Gospel

His work is full of doctrine and piety, and is highly credible

He gives a clear trajectory of the life of Christ, its drama and all its stages—increasing our appreciation and admiration for the God-Man.

If more Catholics knew about works like Coleridge’s, then other works based on sentimentality and dubious private revelations would be much less attractive.

But sourcing and curating the texts, cleaning up scans, and editing them for online reading is a labour of love, and takes a lot of time.

Will you lend us a hand and hit subscribe?

Read next:

Follow our projects on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

St. Matt. xi. 27.

This is St. Mark’s way. When he names Simon of Cyrene, he adds, ‘the father of Alexander and Rufus,’ who seem to have been known to those for whom he wrote (St. Mark xv. 21).