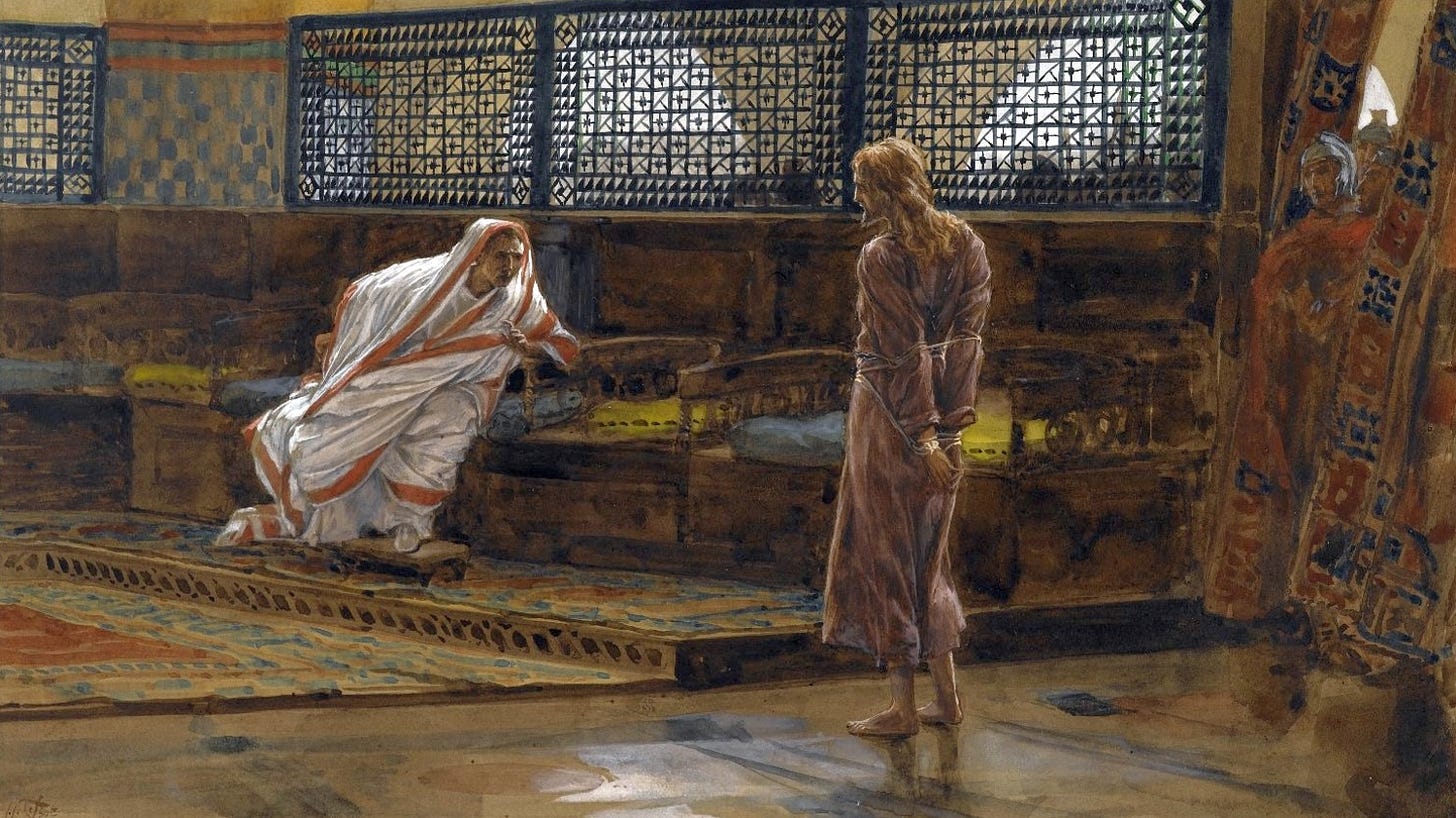

'Art thou a king, then?' Pilate & Christ the King

The Gospel for the feast of Christ the King presents Our Lord, as a prisoner, affirming his kingship to Pilate. What can we learn from this episode about Christ as King—and about Pilate himself?

The social kingship of Christ—that is, his sovereignty over society—is the doctrine which is called into question in our time. This is why it is such a key theme for traditional Catholics; and we have written about it many times at The WM Review.

However, while we are reacting to the eclipse of Christ’s social kingship, it is important not to forget other truths that this feast presents.

In that vein, the Gospel for the feast presents Christ declaring his kingship before Pilate, crowned with thorns, and showing what kind of King he really is.

In this chapter, Fr Coleridge tells us…

What Pilate would have made of the Jerusalem priests and leaders

How Pilate would have been a typical example of a Roman leader

Why Christ treated him differently to Caiphas and Herod—and what that shows us about Christ’s priorities and joys.

See also:

Pilate and Christ the King

From

The Passage of Our Lord to the Father

Fr Henry James Coleridge, 1892, Ch. VIII, pp 151-162

St. Matt. xxvii. 11-25; St. Mark xv. 2-14; St. Luke xxiii. 2-17; St. John xviii. 28-40; Story of the Gospels, §§ 165-167.

(Read at Holy Mass on Christ the King)

Pilate himself

The immediate action of the Jewish authorities in the case of our Lord came to an end, as has been said, in the handing over by them of their prisoner, already condemned by them to death, to the Roman Governor, Pontius Pilate.

They were glad in their own minds to have to do this, because, although it was an acknowledgment on their part of their subjection to a foreign jurisdiction, and so far, a humiliation to their pride and feeling of independence, it enabled them to expect that the death of our Lord would be the infliction of the Roman punishment of crucifixion, a more painful and more ignominious death than any permitted by the Jewish code.

Perhaps they were not sorry to have it said that the Man Whom the people had so much honoured had been brought to His end by other hands than theirs.

But our Lord Himself had foretold that He was to die by the hands of the Gentiles for a higher and more Divine reason than the personal spite and jealousy of these Chief Priests. Thus in obedience to the Divine will, as to the manner of the death by which the salvation of the world was to be brought about, these priests themselves were the instruments by whom, as one who was at the time a student in their school at the feet of Gamaliel, pointed out some years after, ‘Christ redeemed us from the curse of the Law, being made a curse for us, as it is written, ‘Cursed is every one that hangeth on a tree.’1

Thus all the agents in this condemnation of our Saviour to this particular death were co-operating in the deliverance of those under the Law from the burden of the curse which St. Paul mentions in the same passage, ‘Cursed is every one that abideth not in all things which are written in the book of the Law to do them.’

The arrangement of Providence

Much has been said and written on the character of this Pontius Pilate, of whom we have to hear so much in the ensuing history.

He displays himself, as far as we are concerned with him, sufficiently in the accounts of the Evangelists, and we are without any other information on which we can rely. Our interest in him arises from the manner in which our Lord dealt with him, and the patient efforts which He made to do him good.

We may take him as an average Roman, neither better nor worse than others of the class to which he belonged. He had probably a considerable dislike, perhaps a contempt, for the Chief Priests, with whom he must have had many dealings, in the course of which he must have become acquainted with the personal characters of many—their ambitions, their unscrupulousness, their not very correct lives, their use of their great position for their own interests, their animosities, and their profound hypocrisies.

They were not the best specimens of their nation, not the men who might have silently influenced a Pagan of his position to thoughts which might have led him to some better knowledge of the true God, as Cornelius and other heathen with whom we meet in the sacred history seem to have been led. Some of the acts of Pilate, as recorded of him, seem to justify the charges against him of inconsiderate violence and cruelty.

The history shows him as a man of some good instincts and feelings, a man of some amount of natural equity, but not of the moral integrity required in one who had the opportunity of following his instincts of right and justice at the cost of a personal danger to himself.

Pilate a fair specimen of his class—tells the priests to deal with Our Lord themsleves

The earlier Evangelists, who tell us all this history in a summary manner, mention simply that the priests and scribes accused our Lord to Pilate of perverting the nation, and forbidding to give tribute to Cæsar, saying that He is Christ the King. This is the account of St. Luke.

It must be remembered that the crime for which the sentence had been passed was blasphemy, but the priests seem to have no scruple in changing the accusation to suit their own convenience, and the apparent chances that they might succeed in making an impression on the Governor. The last Evangelist is here again our fullest authority. St. John’s account is this:

‘Then they led Jesus from Caiphas to the Governor’s hall, and it was morning, and they went not into the hall, that they might not be defiled, but that they might eat the Pasch. Pilate therefore went out to them, and said, What accusation bring you against this Man?

‘They answered and said to him, If He were not a malefactor, we should not have delivered Him to thee. Pilate said to them, Take ye Him, and judge Him according to your law. The Jews, therefore, said to him, It is not lawful for us to put any one to death. That the word of Jesus might be fulfilled which He said, signifying what death He should die.’

The accusation required—not lawful to execute

St. John here throws much light on the history which is imperfect without him. In the first place, we gain from him a new light on the characters of the priests who were so careful to observe ceremonial prescriptions, and to keep up the strict rules about the legal defilements which might be incurred by their violation, at the very time when they were changing the charge on which they expected the Governor to take for granted the justice of a condemnation, which they did not even allege truly, as to the charge on which it had been passed.

This is a members’ article.

Sourcing and curating the texts, cleaning up scans, and editing them for online reading is a labour of love, and takes a lot of time.

If you value what we’re doing at The Father Coleridge Reader, will you give us a hand and keep the project alive?