How did the Centurion’s words come to be said at every Mass?

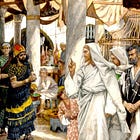

'Lord, I am not worthy'—few men have their words repeated so many times, down so many centuries, as this humble Roman Centurion.

'Lord, I am not worthy'—few men have their words repeated so many times, down so many centuries, as this humble Roman Centurion.

Editors’ Notes

In this part, Father Coleridge tells us…

What the tradition suggests happened to the Centurion after the miracle

How the Church daily repeats the Centurion’s words— “Lord, I am not worthy”—at the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass

What it means for them to appear at the very moment of the consummation of the Holy Sacrifice

Coleridge shows us how extraordinary it is that the words of this Roman Centurion are forever woven into the Church’s highest act of worship, enshrining his humility and faith as the enduring example for approaching the Holy Eucharist.

In the previous part, we compared Fr Coleridge’s explanation of the Gospels with the presentation in The Chosen series.

The Centurion whose servant is healed is a key character in the popular series The Chosen, and the story arc for ‘Gaius’ is crucial for driving the series forward.

But how accurately does it portray him? What does the series get right, and where might it have missed the mark?

See here for more:

This is an ongoing mini-series on Fr Coleridge’s presentation of this incident in the Gospels. It deals with the faith of the Centurion, and Our Lord’s reaction to it:

It also deals with the warning this incident provoked Our Lord to give to the chosen people:

In this final part, Coleridge considers what the Centurion did after this miraculous healing—and his “afterlife” in the Church and her liturgy.

Hit SUBSCRIBE now, so as not to miss the next ones:

The Centurion’s Servant

From

The Training of the Apostles—Part II

Fr Henry James Coleridge SJ

1882, Ch. X

St. Matt. viii. 5–13; St. Luke vii. 1–10

Story of the Gospels, § 50

Third Sunday after Epiphany

Tradition about the Centurion

The accounts end here abruptly, and nothing is said of the Centurion hastening home, or of the other servants coming in joy to greet him with the news.

It may be thought that if our Lord had visited the house, on His way to which the master had sent Him, we should have been told of it. But all these matters are left for the Christian imagination to supply, the sacred writers contenting themselves, in this as in all other such instances, with the simple statement of the facts which were essential for their narrative.

Tradition tells of the conversion of the Centurion to the faith in consequence of this miracle, and he is said, after the Resurrection of our Lord, to have become a Christian preacher. But as far as the narrative of the Evangelist is concerned, we part from him here, and the services he may have rendered to the cause of our Lord will be revealed only in the Kingdom of Heaven.

Or rather, perhaps it may be said, we do not part from him here.

‘Domine, non sum dignus’

His words are ever in the ears of the devout worshippers in Christian churches, for they are taken up by the Church in her Holy Mass, and are perpetually repeated, both by priests and people, or at least in the name of the people, as by priests in their own name, before the reception of the highest privilege bestowed permanently on mankind, the reception of the blessed Body and Blood of our Lord in Holy Communion.

Thousands and thousands of times every day, all over the world, are the words repeated:

‘Lord, I am not worthy that Thou shouldst enter under my roof, but only say the word and my soul shall be healed.’

And those who repeat these words do not utter them in the thought or expectation or desire that our Lord will turn away from them, as if taking them at their word, but simply because the words live on in the Church as the best expression of that humility which is so pleasing to God that to it He can deny nothing.

Whether our Lord entered under the roof of the Centurion, we are nowhere told, but we know that it would be ill for us if He did not enter really and truly under the roof of our mouths and into our hearts and bodies in His Sacramental Presence, there to confer on us benefits and blessings far greater than even the healing of bodily diseases.

The Church’s adoption of his words

It is not, as we know, often that the Holy Catholic Church adopts words in this manner, and the words which she most continually uses in her addresses to God, and our Lord, or our Blessed Lady, are the words of angels, or of great saints, or the words taught us by our Lord Himself.

But this poor heathen Centurion has been made, in a certain sense, the teacher of Christian devotion to all times and generations, and we learn from him that there is no more certain way of gaining a boon from our Lord than the heartfelt profession of our utter unworthiness to receive it, and of His absolute power to give us the substance of what we are in need of in any way that pleases Him.

So St. Peter confessed, after the first miraculous fishing, ‘Depart from me, for I am a sinful man, O Lord,’ not wishing, certainly, that our Lord should leave him, but pouring out to Him the genuine and most prevailing confession of his own unfitness for the harbouring of so great a guest.

Such was the confession which our Lord puts into the mouth of the returning prodigal, ‘Father, I have sinned against Heaven and before thee, I am no more worthy to be called thy son.’

So too the poor leper was content with the prayer, ‘Lord, if Thou wilt, Thou canst make me whole.’

It was this confession of the Omnipotence of God which the Centurion added to that of his own unworthiness, and by so doing, won from our Lord the answer that it should be done to him according to his faith.

And the poor Syrophœnician woman seems to go even one step farther, for she was able to discern the mercifulness as well as the power of our Lord, even through the veil of a first refusal, supported by the statement that He was not sent to such as her:

‘Suffer first the children to be filled, for it is not good to take the bread of the children and cast it to the dogs.’

‘Yea, Lord, for the whelps also eat under the table of the crumbs of the children.’ (St. Mark vii. 27.)

This was a confession, not only of His power and of her unworthiness, but also of the compassionate mercy of His Heart, which was sure to go beyond the special purpose of His formal mission. The words thus involve a principle in the ways of God, the manifest workings of which it would task the sublimest theologians to unfold.

In all these petitions we see the greatness of faith coupled with humility, which delights the Heart of our Lord and is, so to say, irresistible with Him.

End of the mini-series on the Roman Centurion and his servant.

From Fr Henry James Coleridge, The Training of the Apostles—Part II

Here’s why you should subscribe to The Father Coleridge Reader and share with others:

Fr Coleridge provides solid explanations of the entirety of the Gospel

His work is full of doctrine and piety, and is highly credible

He gives a clear trajectory of the life of Christ, its drama and all its stages—increasing our appreciation and admiration for the God-Man.

If more Catholics knew about works like Coleridge’s, then other works based on sentimentality and dubious private revelations would be much less attractive.

But sourcing and curating the texts, cleaning up scans, and editing them for online reading is a labour of love, and takes a lot of time.

Will you lend us a hand and hit subscribe?

Read next:

Follow our projects on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram: