What did 'The Chosen' get right with 'Gaius' the Centurion?

'The Chosen' presents a compelling arc for 'Gaius' the Centurion, but how far is it based on the Gospels?

'The Chosen' presents a compelling arc for 'Gaius' the Centurion, but how far is it based on the Gospels?

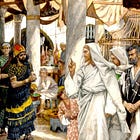

The Centurion whose servant is healed is a key character in the popular series The Chosen, and the story arc for ‘Gaius’ is crucial for driving the series forward.

But how accurately does it portray him? What does the series get right, and where might it have missed the mark?

This is the first of a few articles on Fr Coleridge’s presentation of this incident in the Gospels. Hit SUBSCRIBE now, so as not to miss the next ones.

Gaius in The Chosen

The Chosen focuses on humanising the Centurion as the Gaius character, and connecting him to the broader narrative of Roman and Jewish interactions.

He is portrayed as a Roman Centurion with a personal connection to Matthew and a developing curiosity about Jesus, creating a fictionalised backstory to give emotional depth to his character.

He is depicted as a man on a journey of faith, grappling with his Germanic background and Roman position, along with his progressive awareness of Jesus’ significance.

His motivations are tied to personal loyalty and compassion, particularly for his servant, with an emphasis on his inner moral struggle. To some degree, he is conflated with the nobleman of Capharnaum.

There is no doubt that The Chosen uses these events from the Gospel to great dramatic and emotional impact. Its presentation of Gaius was a slow-burner, with many speculating exactly when and how he would come to bring his petition to Christ.

The Centurion in the Gospels

By contrast, the Centurion of the Gospels remains unnamed and is primarily defined by his faith, humility, and charity, with no mention of personal relationships or prior encounters with Jesus’ disciples. Fr Coleridge, however, proposes ideas based on the nature of a town like Capharnaum.

While Gaius is a man on a journey, the Centurion of the Gospels is presented as a man who has already reached a profound understanding of Jesus’ authority, reasoning that Christ’s divine power can heal with a word, without needing to visit in person.

He is described as genuinely loving the Jewish nation and himself being highly respected by the Jewish elders, who advocate on his behalf to Jesus.

He is an entirely distinct personage to the nobleman of Capharnaum. Although The Chosen finds quite a neat way of conflating them, this conflation does flatten the theological contrasts discussed below.

All in all, the Gospels present the Centurion as a “typological” figure whose individual approach to Christ foreshadows the call of the Gentiles into the Church.

This is precisely the presentation of Fr Coleridge.

For those new here

Who was Coleridge, and why should we care what he says?

Father Henry James Coleridge SJ was a nineteenth century English Jesuit priest, and a forgotten hero.

Among his many achievements, his The Life of Our Life series stands tall. This consisted of over 20 books of commentary on the life of Christ, and was responsible for an influential harmonisation of the four Gospels.

Coleridge provides solid explanations of the entirety of the Gospel

His work is full of doctrine and piety, and is highly credible

He gives a clear trajectory of the life of Christ and all its stages.

If more Catholics knew about works like Fr Coleridge’s, then other works based on sentimentality, or dubious private revelations, would be far less attractive.

One would also hope that non-Catholics who appreciate The Chosen might also appreciate Coleridge’s commentary below.

This website, The Father Coleridge Reader is a gateway to his spiritual writings on Our Lord Jesus Christ, the Holy Gospels, and the life of each Christian today.

In his commentary on this piece, Father Coleridge tells us:

What the story of the Centurion and his servant reveals about faith, humility, and divine authority.

Why the Centurion’s understanding of Christ’s power sets him apart from others at the time, demonstrating a supernatural faith rooted also in both reason.

What lessons this miracle offers about God’s universal mission, breaking down barriers between Jews and Gentiles.

He shows us that the Centurion’s faith and charity reflect the universal scope of Christ’s mission.

This is the first of a few articles on Fr Coleridge’s presentation of this incident in the Gospels.

Hit SUBSCRIBE now, so as not to miss the next ones:

The Centurion’s Servant

From

The Training of the Apostles—Part II

Fr Henry James Coleridge SJ

1882, Ch. X

St. Matt. viii. 5–13; St. Luke vii. 1–10

Story of the Gospels, § 50

Third Sunday after Epiphany

Order of events

We now come to some incidents of this second year of our Lord’s preaching as to the date of which we have no precise guidance.

It has already been said that the Sermon on the Plain was probably delivered early in the summer, after the Pasch at which our Lord healed the impotent man at the Pool of Bethsaida in Jerusalem.

Close on this Pasch followed the return of our Lord to Galilee, and the league formed against Him by the ecclesiastical rulers with the political servants of the Tetrarch. It was a coalition of very incongruous elements, but it was clearly as much to the interest of Herod to suppress any movement by which the peace of the country might be endangered, as it was to the interest of the priests at Jerusalem to oppose the influence of One Who was certainly not of themselves. We have seen that our Lord retired before the coalition, and that He made at this time the selection of the twelve to be His Apostles.

The Sermon on the Plain then followed. And it is not a fanciful conjecture to place these two signal events about the time of the feast of Pentecost after the second Pasch.

The next great event in the preaching of our Lord was the return to Capharnaum, after which He began to teach the people by parables only—a change in His method which attracted the wonder and caused the inquiries of the disciples themselves.

This beginning of the teaching by parables is very probably to be placed about the time of the seed-sowing for the harvest of the next year, that is, in the later months of the year to which the events already mentioned belonged. This date is made probable by the subject of the first and succeeding parables. It was so very much our Lord’s habit to take the text, so to say, of His teaching from the natural objects and scenes around Him at the time, that we can hardly doubt that He chose the imagery of this first series of parables in this manner, and that the fields were actually being sown at the time at which He spoke.

If this be so, and if the Sermon on the Plain be rightly placed about the feast of Pentecost, it would follow that an interval of several months occurred, immediately after the delivery of that Sermon, and before the beginning of the parables.

During this interval we have little to guide us as to the exact dates of the few incidents which are recorded, though we may fairly trust the order in which they are arranged by the most historical of the Evangelists, St. Luke.

Our Lord on His missionary circuits

There is nothing in this that ought to be surprising to those who are, to some extent, familiar with the manner in which our Lord spent so much of His time during His Public Life.

We already know that He passed large portions of the most active part of His career in Galilee, and afterwards in Judea, in missionary circuits throughout the country, the events and occupations of which were very much the same day after day, except that He was constantly changing the scene of His labours. Periods of activity of this kind are in one sense most full of incidents of importance, for nothing can be more important in the history of the Kingdom of God than the conversion of souls, and these periods were in this respect most fruitful.

But in another sense they are marked by a great sameness, and the history which serves for one week or month would be almost equally suited to another. Thus it is not the custom of the Evangelists to speak of these circuits except in the most summary manner.

Our Lord again at Capharnaum

But it would often happen that the sameness of these periods would be broken by some remarkably striking incidents of mercy or power, and it is natural that such incidents should not be passed over in the sacred history.

They would be exceptional features in the general picture, for which, as such, a few words would suffice. Such are the few incidents which, as is clear from the order of St. Luke, belong to this period, that is, between the Sermon on the Plain and the delivery of the first great series of the Parables of our Lord.

The miracle of which we are now to speak was in some important respects singular and unprecedented in the Ministry of our Lord, and it was made by Him the occasion of a warning to some of those who were hanging back in their adhesion to Him, of which the Evangelists had afterwards many reasons for seeing the significance. We know that, even during the circuits of the first year of His Galilean preaching, our Blessed Lord was for long seasons together absent from Capharnaum, the place which, nevertheless, had gained the name of being His own city.

Much more was He likely to absent Himself from it for long intervals during this the second year of His preaching. But He would often have occasion to visit it from time to time. One of these visits was made, as St. Luke tells us, at the conclusion of one of the circuits of which we are speaking, and which is hinted at rather than directly mentioned in the narrative of the Evangelists. St. Luke says, ‘And when He had finished all His words in the hearing of the people, He entered into Capharnaum.’

Here it was that the occasion of the miracle was awaiting Him.

‘And the servant of a certain Centurion, who was dear to him, being sick, was ready to die. And when he heard of Jesus, he sent to Him the ancients of the Jews, desiring Him to come and heal his servant. And when they came to Him, they besought Him earnestly, saying to Him, He is worthy that thou shouldst do this thing for him, for he loveth our nation, and he hath built us a synagogue,’ or rather, our synagogue.

The Centurion and his servant

The description of the Centurion and his servant, with the elders of the Jews interceding with our Lord for them, gives us a picture of what was perhaps not uncommon in the mixed society of those times.

In Galilee the Gentiles were much in the minority, while in other parts, outside the precincts of the Holy Land, the Jews would themselves be a small cluster of families in the midst of a heathen population. The Providence of God had been bringing about this intermixture of Jews and Gentiles for many generations, as if to prepare the way, both for the conversion of the heathen, and for the abolition of the distinction between the two in the Christian Church.

Up to the time of the Captivity, the Jews had been kept very strictly separate from all other nations, although, after the establishment of the kingdom of David and Solomon, they had had more intercourse than before with neighbouring nations.

But the Captivity itself had acted, in some degree, as a leavening of the Eastern nations by a Jewish influence, not the less strong morally because the Jews were weak. And under the Grecian Empire, which broke down the barrier between the Asiatic and European populations, the Jew had been scattered in large numbers over the whole civilized world.

The Roman Empire contained, we may suppose, many good men in the position of this Centurion, men who had been mixed up by circumstances with Jews in Palestine, or with Jewish settlers in foreign parts, and who had been attracted by the superior purity of their creed or their moral law, by the beauty and reasonableness of their doctrine, and led on to serve the true God in works of charity and piety.

Some of these might have become proselytes in a more formal manner, while others remained at the door, as it were, of the Tabernacle. We gather from the Acts of the Apostles that the attendance in the synagogue was not confined to Jews strictly so called.

The Jews of Capharnaum

This Centurion evidently lived in intimate acquaintanceship with the chief Jews of Capharnaum.

We gather also from the account of St. Luke that not all the Jewish authorities at this time were in league against our Lord. It is probable that the leaders of the opposition to Him came from Jerusalem, emissaries of the Scribes and Pharisees there. These men had known comparatively little of our Lord, of the marvellous works He wrought or the doctrines which He preached. They were simply the instruments of the blind malice and jealousy of their chiefs.

On the other hand, there would be many among those who had known Him and heard Him, who could not take so strong a part against Him as these representatives of the central authority would wish. They may not have been numerous or powerful enough to turn the tide, which was now setting so violently in the direction of hostility to Him, but in their own personal feelings they may still have been on His side.

Such must have been Jairus, the ruler of the synagogue at Capharnaum, such the nobleman whose son had been healed by our Lord more than a year before, and many of the wealthy publicans who had sat with Him at the feast given by St. Matthew.

Virtue of the Centurion

It is not surprising that the Centurion and his friends should have thought that it might require a special force of entreaty and intercession to induce our Blessed Lord to enter the house and listen to the prayer of this good heathen.

Up to this time He had done nothing to intimate directly that He regarded the Gentiles as objects of His mission, nor had He said much about the extension of the privileges of the Kingdom of God beyond the range of the chosen people. Wherever there are privileges in the way of religion and the means of grace, there it is quite certain that there will be some narrow prejudices against the indefinite opening of those privileges to everyone, and a tendency to pride in their possession.

The words of the Jewish elders seem to imply a sort of compassion on their part for the comparative misery of the condition of the Centurion. He might be unworthy, their words imply, of the notice of our Lord, but still he loved the holy nation and he had moreover built for them the synagogue in which God was worshipped, and the Sacred Scriptures read and the holy Law taught, in Capharnaum itself.

It was a great thing for a Roman to overcome his national pride, and lay aside his allegiance to the official religion, which had, as it was thought, done so much towards the establishment of the worldwide Empire of the great city of the Tiber. It was a great thing that he had had simplicity and humility enough to recognise the superiority of the Jewish morality, and of the worship of the One God.

Deep in the hearts and conscience of the good heathen lay the germs of natural religion, of which, in truth, the revelation possessed by the Jews was the Divine superstructure, requiring that other as its own foundation. Where natural religion had not been overlaid and corrupted and obscured by the bad traditions of the false polytheism and low morality which prevailed, even among the most cultivated nations of the Pagan world, there were the instincts of which revelation was the natural satisfaction.

Thus the good heathen could not be true to his own best thoughts and the teachings of his conscience, without being prepared for Divine Revelation, and, when he came across it, it was to be seen whether he could overcome the traditional repugnance of his own proud and conquering nation.

The case is exactly repeated in the case of the good Christian who has been brought up outside the Catholic Church, and who has been taught concerning her a number of those malignant falsehoods, of which the greater part of anti-Catholic controversy is made up. He is strongly drawn by the beauty and authority and unity of the Church, but can he overcome his prejudices? Or will he turn away like Naaman, indignant at what he conceives to be a humiliating doctrine for his own nation?

This is an issue which, in our own times and country, has to be settled, day after day, in a score of instances.

His acquaintance with the Jewish religion

The Centurion had long ago laid aside his prejudice against the Jews and their religion.

He had come to love them for the sake of their creed, which promised so much to the yearnings after truth of which he had long been conscious, and he had contributed to the worship and honour of the God of Israel in a way which is seldom left without its reward, even when the churches and sacred edifices, which are raised by a mistaken devotion, are handed over to the imperfect worship of a schismatical community.

But God had given him greater gifts than the simple recognition of the truth of Judaism. We may gather from his care of his servant that he was a good and affectionate master, and we certainly learn from his own words that he was a thoughtful ponderer of the ways of God, and had arrived at a very high notion of the dignity of our Lord’s Person.

It is hard to think that he did not understand even the Divine character of our Lord.

The nobleman of Capharnaum

His case is the exact counterpart of that of the man who was probably his friend, the nobleman who had met our Lord at Cana the year before, and begged Him to come down and heal his son at Capharnaum.

The heart of the Centurion had treasured that incident, and now he was to show the fruit which it had produced in his own thoughts concerning our Lord. Unreflecting men are always inclined to limit the goodness, and even the power, of God to that of which they have found evidence or declaration, forgetting that whatever God does, or declares concerning Himself, is but a partial manifestation of His character and attributes, and that all such manifestations are meant to hint at a great deal more than they actually reveal.

This dullness lies at the foundation of the extreme reluctance which men show as to admitting anything like a miracle beyond what is written in Scripture, if even that—as if the power which enacted the laws of nature could not go beyond them, as if the very fact that God does so many wonderful things ordinarily was a proof that He could do nothing extraordinarily.

Just as without the constant witness of the written Law men forgot even some of the plainest conclusions involved in the first principles of the natural Law—as was especially the case with regard to all that concerned purity—so many things which seem to Catholics as evidently true, though not actually written in Scripture, as with regard to the position, for example, of our Blessed Lady and the Saints in the Kingdom of Heaven, are challenged by Protestants as contrary to the very spirit of revelation.

It is to such cases that St. Ignatius applies our Lord’s words to His Apostles: ‘Do not you yet know nor understand?’ implying that God means us to reason reverently on the principles and truths and facts of faith and revelation and experience, and that He does not make every natural conclusion therefrom a matter of special revelation. The Centurion had simply reasoned from what was certain concerning our Lord’s power and mercy, and yet he had reached a point in the faith which so many others had not attained.

From Fr Henry James Coleridge, The Training of the Apostles—Part II

In the next part, Father Coleridge will tell us…

Why the Centurion, unlike others, recognised that Christ’s authority over life and death did not require His physical presence.

How the Centurion’s profound humility and faith contrasted with the pride and scepticism of many among the once-chosen people.

What this moment foreshadows about the inclusion of Gentiles in God’s Kingdom and the rejection of the unfaithful among Israel.

He will show us that the Centurion’s faith—marked by his belief in Christ’s word alone—provides a model for the Church, where trust in divine authority surpasses visible signs and points to the universal scope of salvation.

Subscribe now and make sure you don’t miss this:

Here’s why you should subscribe to The Father Coleridge Reader and share with others:

Fr Coleridge provides solid explanations of the entirety of the Gospel

His work is full of doctrine and piety, and is highly credible

He gives a clear trajectory of the life of Christ, its drama and all its stages—increasing our appreciation and admiration for the God-Man.

If more Catholics knew about works like Coleridge’s, then other works based on sentimentality and dubious private revelations would be much less attractive.

But sourcing and curating the texts, cleaning up scans, and editing them for online reading is a labour of love, and takes a lot of time.

Will you lend us a hand and hit subscribe?

Read next:

Follow our projects on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram: