The Beatitudes—why Christ says the persecuted and poor are 'blessed'

Why does Christ declare that the persecuted, poor, mourners and other unlikely groups are 'blessed'—or even 'happy'—at the start of the Sermon on the Mount—and what does this show us about wisdom?

In the Roman Rite, the Gospel for the Mass of All Saints is that of the Beatitudes.

In this chapter, Fr Coleridge tells us…

The relationship between the Beatitudes and the Ten Commandments

How the Beatitudes are CENTRAL to the Christian life

How they represent the goal of how we should view the world.

See also:

The Beatitudes

From

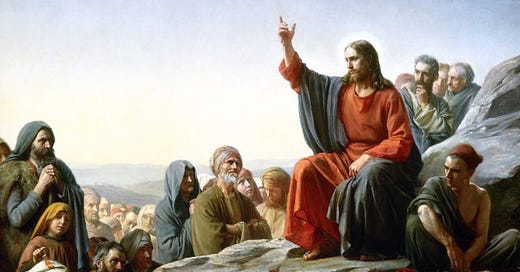

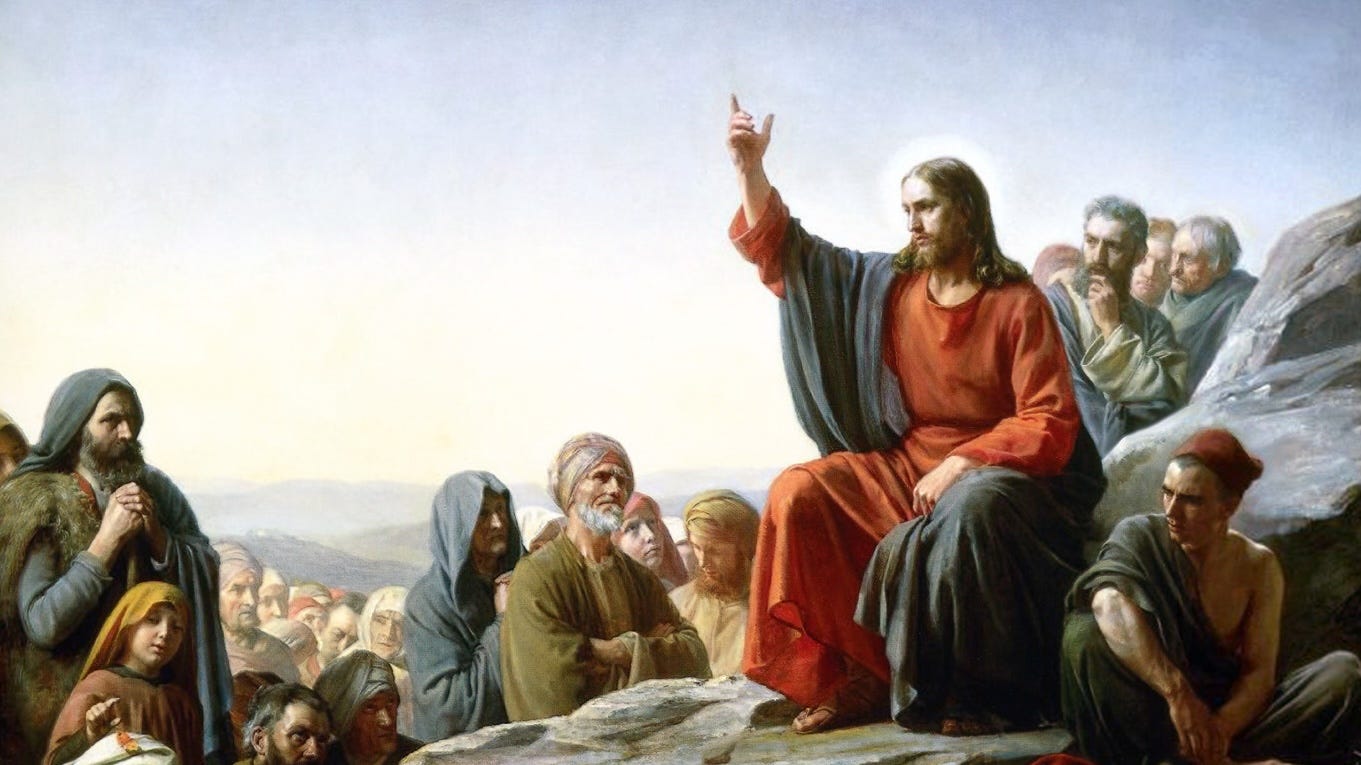

The Preaching of the Beatitudes

Fr Henry James Coleridge, 1876, Ch. IX, pp 136-149

St. Matt. v. 3-10; Story of the Gospels, § 31

Brevity and pregnancy of the Beatitudes

It has already been remarked that the doctrines set forth with so much solemnity and authority in the Sermon on the Mount, containing as they do the most sublime Christian philosophy, are yet couched by our Lord in the simplest, shortest, and most pregnant language, like so many aphorisms or proverbs, and that, in this brevity and pregnancy, they remind us of the form in which so many great principles of the natural law of morality were summed up and promulgated in the Code which was delivered on Mount Sinai.

This remark applies especially to the Beatitudes, with which the Sermon on the Mount begins. There are other pregnant sayings and precepts in the Sermon on the Mount which are delivered by our Lord in the same royal tone of authority. But in many parts of the discourse before us it does not differ so much as in the opening clauses from other discourses which occur in the Gospels, in regard of the amount of development and expression which is given to the thoughts which are therein contained.

Thus the Beatitudes have a character of their own, as compared with the rest of the Sermon, both as to their substance and as to the form in which they are delivered, and in this respect they may be compared to the Decalogue itself, as contrasted with the many other moral rules and precepts which occur in the Book of Exodus or of Deuteronomy.

We can hardly be wrong in considering them in the light of this resemblance to the Decalogue as to the importance of their teaching, the position which they occupy in the legislation of the New Kingdom, and the particular form in which they are promulgated.

The new Creation

Some of the ancient writers have compared the words in which our Lord has laid down these great laws of His Kingdom, to the blessing spoken of in the first chapter of Genesis, when God saw what He had made, and that it was good, and blessed it, and they have seen in the solemn benedictions here pronounced by the Founder of the New Creation an indication of His identity with the God Who made the world.

Thus, when our Lord blessed the virtues or habits which are crowned in the Beatitudes, He blessed the work of His own hands, a new creation of grace far more beautiful and noble than the natural man, which was to reflect in every line His own image and likeness, and to derive from Him its fruitfulness and power and felicity.

The natural man grows and develops and operates and arrives at maturity by the silent working of the elements and vital principles of which his frame and substance are made up, under the blessing of his Creator: his relations with the universe around him, what he takes from it, what he gives to it, are the results of these conditions of his nature.

The new creature who is formed and fashioned by the Holy Ghost after the image of Christ, has to take his own part, under the guidance of grace, in his own growth to maturity and perfection, and the development of the spiritual powers which are given him in his new birth. And the laws and lines of his advance to the ripe fulness of strength and beauty which God designs for him are traced in the Beatitudes.

They are no chance enumeration of blessed qualities which might be otherwise arranged or to which more might be added, nor are their rewards accidental or distributed at random, or the mere undeserved bounty bestowed by royal munificence on qualities which have no correspondence with the blessings which they receive. The grace which generates them is gratuitous, the glory which crowns them is their own by the laws of the Kingdom of God.

Relation of the virtues and rewards

Thus it has been remarked that our Lord does not say that He will give the kingdom of heaven to the poor in spirit, or that He will make the meek possess the earth, or that He will show mercy unto the merciful, and so with the rest, though such language would certainly have been most true as well as most consoling; but He uses the form, that the kingdom of heaven is of the poor in spirit, and the like, in order that the reward may be understood to grow out of the virtue as the fruit out of the plant.

Thus we may understand the remark of many Christian authors who have written on these Beatitudes, that the blessing which our Lord affirms and decrees is twofold in each case, that is, that the virtue itself is blessed, and it is further blessed in that it has the reward and crown and fruit which He attaches to it. So that if by possibility, or for a time, the meek should not ‘inherit (or possess) the land,’ or the mourners not be comforted, or those who hunger and thirst after justice should not be satisfied, still they would be blessed because they are what they are.

For each Beatitude, as distinct from the reward of which it is the condition and foundation, is an aspect of the perfect soul resting in its own pure tranquillity and peace in the arms of its Father and God, and as a wonderful gem, blazing with inherent brilliancy, may be different in hue or form as its different faces are looked on, and as the gem is what it is even though it have no rich setting, nor be worn in the crown of a king, so the perfect soul has always its own blessedness inherent in itself, or rather it is never shut out from the sight of Him to see Whom is to be blessed.

What is a ‘Beatitude’

We find spiritual theologians, in accordance with this doctrine, assigning the highest place of all in the scale of states of the soul to these Beatitudes considered as such.

The delicate system on which the arrangement is made need not be entered upon here in any fulness of detail, but it may be well shortly to allude to it. St. Bernardine of Siena1 tells us that there are five degrees of grace, by which the soul in the present life is led to the state of Beatitude.

‘The first is sacramental grace, the second is virtue, the third the gifts of the Holy Ghost, the fourth the fruits of the same, and the fifth the Beatitudes.’

Sacramental grace heals the soul. The sacraments are the medicines and remedies against vices, and thus their grace does away with sickness. The virtues give the faculties power to act well. He is looking upon all these five principles as causes of ‘purgation,’ and so he says that the virtues do away with the soul’s weakness, giving it strength to operate.

We have already mentioned that the virtues produce good acts of the ordinary kind and in the ordinary way, according to reason, natural or supernatural. The gifts of the Holy Ghost do away with all difficulty in working good, enabling the soul to work with facility and quickness: they also, as has been said before, are the principles of heroic acts of virtue, and of acts which might not be thought of or might not be prudent on ordinary grounds, but which are suggested and made possible and easy by the gifts of the Holy Ghost.

The fruits add the crown of joy and satisfaction to the good works of either kind, and in their ‘purgative’ character they do away with all weariness, fatigue, or sense of effort in such works. Higher than all are the Beatitudes—‘the state and perfection of a soul already entirely purified.’

He gives the definition of ‘Beatitude’—‘A grace known to one who is truly wise, tending to produce sweetness of conscience, and already close on the borders of glory.’

It is a kind of grace, because it pre-supposes the habits of the virtues and the gifts informed by charity and grace, so as to make a man rightly and easily and joyfully undergo adversities, undertake difficult things, and work the works of perfection and supererogation. It is a kind of grace known to the truly wise, because it seems quite foreign to the opinions of human wisdom.

St. Bernardine’s definition

All the Beatitudes, according to the opinion of the world, have misery as their companion or as their predecessor. He quotes St. Bernard, who says, ‘What is so hidden, as that poverty is blessed?’

And in St. Matthew our Lord says, ‘I confess to Thee, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, because Thou hast hid these things from the wise and prudent,’2 that is, of this world.

For these things cannot be perfectly known except one has had some experience and taste of God. Then again, the definition speaks of ‘sweetness’ of conscience, because a Beatitude is the perfection of a soul already purified, and it preserves the mind from all remorse and reproach of conscience, and thus disposes it to a sweet and happy life.

And lastly, it is added, that the grace of the Beatitudes is already, as it were, on the borders of glory, for it is after all the blessedness of men still in their state of pilgrimage, not yet arrived at their home and country, whom it makes blessed in hope, and in a certain sense actually blessed also, because it gives them a certain nearness and easiness of approach to God.

Principles of holiness

This must suffice as to the perfection of the state of the soul in which the Beatitudes reside in their highest stage. It is at once obvious that the holy writers who speak of them in this almost technical manner have before their minds a generic condition of consummate sanctity, which might be conceived of other virtuous habits of the soul as well as of those particular excellences which are declared by our Lord to be Blessed.

Our present business is rather with the Beatitudes as principles of holiness, and lines, so to speak, of perfection, which may admit of many degrees between that stage of virtue which is obligatory on all under pain of sin, and the high and beautiful serenity which belongs to the state of the soul on which we have been dwelling.

Thus there are some acts of poverty of spirit or of purity of heart which are essential to the state of grace itself, and which may be produced by virtue of the sacraments. There may be other acts which require the habits of virtue, and others which are more extraordinary, and may be the result of the gifts of the Holy Ghost; others which may show the influence of His fruits, and others which may belong to the full and perfect Beatitude.

When the Beatitudes are considered severally, it will be natural to inquire why these particular habits or virtues or states of the soul have been selected by our Lord rather than any others, why they have been arranged by Him in the order in which we have received them, and why He has connected with each one of them that particular reward or crown which He has assigned.

For the present we consider them in general as the great principles and laws of the new kingdom of which our Lord is King—a kingdom, as He Himself said to Pilate, not of this world, but still in the world, and as truly a kingdom with its laws and character and spirit, its organization and variety of grades and ranks, its authorities and its subjects, as the Empire of Macedon or Rome or Persia or Assyria.

When our Lord speaks of Beatitude in connection with this kingdom and its subjects, He speaks of what sums up in itself the formal end for which that kingdom has been created and exists. For the beatitude of man is the glory of God, and these two ends are substantially the same.

The Kingdom of our Lord has for its end the glory of God by means of the beatitude of man, and the beatitude of man by means of his perfection, of which perfection He Himself is the normal type as well as the instrumental and meritorious cause.

How far obligatory—contrast with the Decalogue

This enables us to see the answer to the question how far the Beatitudes, being the laws of the New Kingdom, are obligatory on all its citizens. They are obligatory in so far as the perfection, which is the intention of God in founding it, is obligatory on its several members and on the whole body.

Here again, we are struck with the contrast between the new and the old Legislation. We naturally speak of the precepts of the Decalogue, forgetting that they are almost exclusively in form only prohibitions. They set forth certain principles of the eternal law of morality by taking them, as it were, at the lowest possible point, at which their violation sinks to the level of direct grievous sin of the most obvious and unquestionable heinousness.

The letter of the law forbids, for instance, murder and adultery; and yet we instinctively feel that the principles of the natural law which are thus defended, as it were, on their remotest frontier, enact the custody of the thoughts and desires of the heart as well as the abstinence from outward sin, and that they are touched by any infringement of purity or charity of the most subtle kind.

Thus the faithful Christian who passes his life in the strength of sacramental grace and of the indwelling of the Holy Ghost, free from any serious deliberate sin whatever, can find in the prohibitions of the Decalogue, as he is taught to understand them, an adequate code for his own continual self-examination. They appeal, in truth, to the motive of fear, and teach perfection by striking peremptorily upon the external acts by which the principles which they embody are violated.

There are no particular punishments threatened for particular crimes, for the violation of the prohibitions involves the anger of God the Lawgiver in the first instance, and thus ensures the most terrible punishment.

Appeal to hope

But the Legislation of the New Kingdom appeals to the motive of hope. The use of this motive, and of numberless particular promises to enforce it, is characteristic of our Blessed Lord. He is all bounty and munificence, His hands full of blessings, which He is yearning to bestow, and His promises, of which He is profuse, are the anticipations of the joy which will be when He actually bestows them, not in the way of mere bounty, but as rewards held out and won and then bestowed.

Such a Legislator naturally puts forward the highest grade of the perfection which He desires and the noblest form of the recompense which He promises. There are certainly degrees in which the virtues of the Beatitudes are necessary to and obligatory upon all Christians. In some measure, poverty of spirit, meekness, mercifulness, purity of heart, are needful for salvation itself. The lofty teaching of the Christian code does not raise these degrees, nor abolish the compassionate mercy of God, according to which nothing but mortal sin can destroy the life of the soul.

But the very form of the new commandments encourages men to press on very far beyond what must be observed under pain of sin, and these commandments enjoin an immense range of acts and habits which are, strictly speaking, and in general, matters of counsel rather than matters of obligation.

Beatitudes open to all

And yet, high as is the sphere of the Beatitudes, they are still within the reach of all, in that they require no particular state of life or external vocation in those who may attain them even in their greatest perfection. The richest prince may be poor in spirit, the ruler of half the world, the most exalted in intellect or rank or influence, may be meek, the poorest labourer or the busiest merchant or lawyer may hunger and thirst after justice, and be clean of heart.

There are in the Kingdom of God, in its present phase, differences of vocations and states, which require, and are supplied with, graces of a lower or a higher order for their due discharge; but these differences have no effect as to the attainment of the Beatitudes. Ecclesiastics and lay people, religious and seculars, spiritual rulers and the lowest of their subjects, are on a level as to the principles which are here embodied, which require perfection of the highest kind for their full possession, from which, nevertheless, no one is debarred.

In the same way, the order of graces which are known by the name of gratiæ gratis data, miracles, prophecy, the power of healing, the discernment of spirits, and the like, are no passports to the Beatitudes, nor does their absence from any soul prevent the presence of the latter in all their fulness.

Their relation to the heavenly state

In thus rising beyond and above all the accidental and transient distinctions which divide the citizens of the kingdom of heaven in its present stage, however important those distinctions may be in themselves and in their possible consequences, the Beatitudes reveal their own essential, permanent, and fundamental relations to that future state of the children of God from which their name is derived, and of which they are, as has been said, in some sort an anticipation. They are the lineaments of that character of our Blessed Lord Himself, resemblance to which it is the work of the Holy Ghost to fashion the souls in which He dwells.

They are the true ‘pattern shown on the Mount’3—delivered as precepts on the Mount of the Beatitudes, exemplified in all the words and works of the Lawgiver Himself, and at last nailed to the Cross in His Person on Mount Calvary, where He finally won for those who would follow Him the blessings which He has attached to poverty of spirit, meekness and mourning, to hunger and thirst after justice, to mercifulness and purity of heart, where He was the great Peacemaker because He was the Son of God, and gained the kingdom of heaven because He was persecuted for the sake of justice.

Ther relation to Christian society

In another respect also they seem to anticipate, not only the perfect blessedness of each several soul which will hereafter enjoy the vision of God, but that special feature of the felicity of heaven of which we can at present feel that it will cause some of the tenderest and most exquisite of the joys which await us there, without being able as yet to understand their intensity.

The happiness and perfection of a society must be greater in proportion to the capacity for union and mutual intimacy and affection between its members, and the time for Christians fully to know, perfectly to love and be united one to another, has not yet come. But the Beatitudes have a direct tendency to prepare the way for this perfect society hereafter, and even with regard to the present state of humanity they have an office of this character.

There are sayings and passages in the New Testament which seem to speak in wonderful language of the Body of Christ and the mutual offices of its members. St. Paul, for instance, mentions our Lord as the Head of the Body, unto Whom we are, as he says, ‘to grow up;’ ‘from Whom the whole Body, being compacted and fitly joined together, by what every joint supplieth, according to the operation in the measure of every part, maketh increase of the body unto the edifying of itself in charity.’4

The two societies

The Church is the fulfilment of this description, both in the varied offices of the several members, and in the spirit or life-blood of charity which animates them all and is their bond of union.

But our Blessed Lord, Who has founded the Church, has also elevated and ennobled the natural society of which God when He created man was the author and guardian, and the laws which He has given in the Beatitudes are the principles of that elevation and ennoblement. For the natural and the supernatural societies are identical in their members as in their Author.

It cannot therefore be, that any new and more powerful means of interior and spiritual perfection which He vouchsafes to bestow upon these members should not tend with marvellous force to the good of the society, whether natural or supernatural, which by His ordinance is composed of them. To raise men one by one higher in sanctity and spiritual stature is to make them better for every end for which their Creator intended them, and it belongs to the nature of man, who is made for society, that whatever he gains morally or spiritually for himself he gains for all around him.

If human society were an artificial institution, arranged by mutual compact, and not enacted by the Creator, the Beatitudes which come from Him might come into collision with its principles. As, on the other hand, society is the creation of God, it cannot but be made more perfect and more happy by the working of these great laws.

Characteristics and possible effects of the Beatitudes

Thus, the Beatitudes are, as has been said, the great principles of perfection in the New Kingdom of our Lord, founded upon that clear insight into the truth as to God, ourselves, His rights, and our duties and prospects, and the world around us, which is furnished by the gift of faith, which perfects reason, and is itself brought to perfection by the teaching of the Holy Ghost, in those souls which are obedient to His guidance, and in whom His gifts do not lie idle.

They are promulgated by our Lord with sovereign authority—an authority which, as has been remarked, recalls the act of God in blessing the world which He had made. The very form in which these great principles are set forth reveals the condescending and beneficent character of the King of the New Kingdom; and we may now add that the Beatitudes are so couched as to be the laws of the Christian society as well as of Christian souls, one by one. They have a distinctly social character, and contain the blessing of the world at large, as well as of those persons in whose souls they are made perfect.

The order in which they are arranged, of which more may be said hereafter, is the order of the regeneration of society, and a sort of prophecy of the history of the Church. It is by means of the principles which are embodied in the Beatitudes that a Christian community was formed in the world, which, without altering the natural organization of society, penetrated it in every direction, breathing into it a new life and spirit, and thus healing the wounds and miseries which had so long afflicted mankind.

The actual effects

It is true that never as yet have the principles of the Beatitudes dominated the whole world; and that, when we speak of them as having regenerated society, we speak of their tendency and power rather than of their actual and historical effect.

But the same may be said of any other manifestation of truth or communication of healing grace. The sacrifice of the Cross is of infinite efficacy, and by virtue of it a new Creation has come into existence. But the actual results of what our Lord has done and suffered and purchased correspond rather to the disappointment which He allowed to cloud His soul at the time of the Agony in the Garden, than to the intrinsic power of His work, or even to the glowing language in which the fruit of that work has been described by the Evangelical Prophet.

The souls in which the grace which our Lord has left behind Him is allowed to accomplish all that it can accomplish, are few indeed; and what is true of single souls is true of that multitude and community of single souls of which the Church is made up, and of the teeming world around her, which she has the mission as well as the power to convert and transform and beautify, with all the glories of the creation of grace.

She shows her Divine origin, her heavenly mission, her supernatural gifts, by what she does, because any one of her countless triumphs is the result of a power and a presence which is nothing short of divine. If she had suffered greater losses and endured more relentless opposition and persecution than she has actually suffered, she would still have proved herself to be what she claims to be by evidence which no human reason could gainsay.

But what is enough for testimony is not enough for complete success, and it is for a witness that the Gospel is to be preached to all nations. The gates of hell have never yet prevailed, and never will prevail against her; but she is not until the end entirely to vanquish the gates of hell. The Beatitudes contain a philosophy of Christian life which might long ago have regenerated society, and which can always, as far as it is allowed to work, elevate those whom it penetrates to a state of happy peace and security.

They are fraught with the healing of the nations, and, as far as they have been allowed to work, the nations have been healed. Their power is not less now than when they were first uttered by our Lord upon the Mount. They can never grow old, for they are laws which came from the Heart of Him Who is eternal, Who knows the needs of the creatures He has made, and has power to heal all their maladies.

Over and over again Christian society may become diseased to the core, for the concupiscences of nature are fresh in every succeeding generation and in every child of Adam that comes into the world.

But over and over again Christian society can be healed, for, as the Wise Man says, God ‘hath made the nations of the world for health,’5 and that health is stored up for them in the undying legislation of the Beatitudes.

From Fr Henry James Coleridge, The Preaching of the Beatitudes

If you’re enjoying reading Father Coleridge’s rich explanations of the Gospels and the life of Our Lord, then will you lend us a hand and hit subscribe?

Further Reading:

Follow our projects on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

Sermo de Christianâ perfectione Beatitudinum Evangelicarum, art. 2, c. I.

St. Matt. xi. 25.

Heb. viii. 5, Exodus xxv. 40.

Ephes. iv. 16.

Wisdom i. 14