‘Their Angels see the face of my Father in Heaven’

Why did Our Lord associate avoiding scandal with not offending the guardian angels? Find out in Fr Coleridge's commentary on the passage used for Michaelmas and the other feasts of the holy angels.

‘Their Angels in Heaven always see the face of my Father Who is in Heaven.’

From

The Preaching of the Cross, Part I

Fr Henry James Coleridge, 1886, Ch. VII (‘The Greater in the Kingdom’), pp 120-31

St. Matt. xviii. 1–14; St. Mark ix. 32–49; St. Luke ix. 46–48; Story of the Gospels, § 86-7

(Read at Holy Mass on Michaelmas)

In this chapter…

The evil of scandal

What Our Lord means in his reference to the angels and scandal

How this passage shows what Fr Coleridge calls “the pre-occupation of the Sacred Heart.”

Prior to this section, Fr Coleridge has been discussing the Apostles’ question about who would be the greatest in the Kingdom of Heaven. Our Lord instead talks about “the little ones”, and Fr Coleridge explains what he is teaching the Apostles about the evil of clerical ambition. After setting out a few consequences, the subject turns to that of scandal.

The ‘necessity’ of scandals

When our Lord says that it must needs be that scandals come, He does not of course mean that there is any natural necessity for them, or that God has decreed that they should be. For there can be no scandal without the deliberate and free action of the human will, in the person or persons who cause the scandal, and the wills of men are never constrained by God to do evil, nor is any one held guilty for what he has not done with freedom and deliberation.

The necessity of which our Lord speaks is, in the first instance, the result of the weakness, the blindness, and the malevolence of men, who are prone to what is evil from their youth up, and who live in a world which inherits and propagates the evil maxims and habits of former generations, adding to them from time to time its own new inventions and developments of evil.

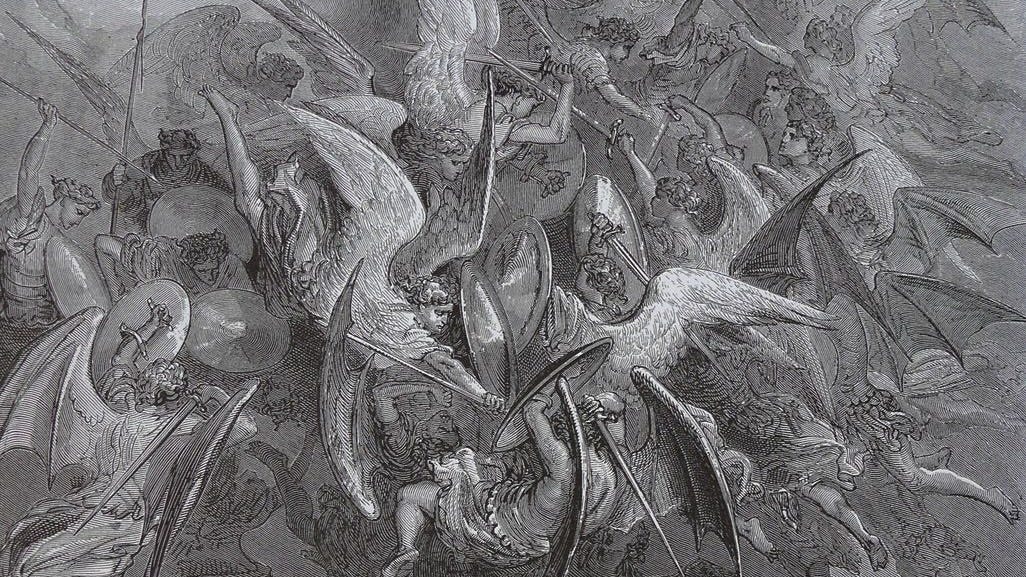

Thus it was certain that, unless God interfered with some preventive action which might violate the freedom of the will, sin would find its way into the world if the time of probation was to be prolonged, as it found its way into Heaven itself among creatures not yet confirmed in grace, in reward for their faithfulness in their appointed trial.

In this sense things must be because they are certain to be. It is certain that even the just cannot altogether escape the falling into imperfections and lighter sins, unless they are prevented by some special magnificence of grace, as was the case with the Blessed Mother of God.

Our lot is cast in a world in which we have all very great influence, for good or for evil, one on another, in which we have to learn one from another what is right and what is wrong, in which the force of example and of the opinion of others is very great, in which temptations are abundant, and the influence of temporal things and matters of sense very much greater, naturally, than that of the truths of faith and the principles of the invisible world.

Moreover, we are in this world for the express purpose of being tried, though assisted with grace if we are faithful, and we are constantly assailed by beings far more powerful by nature than ourselves, whose great aim and delight is to lead us into delusion and persuade us to sin.

In such a world and under such conditions of life, it is morally impossible that there should not be numberless instances of scandal. It is not naturally necessary, but it is reasonably inevitable. It could not be altogether prevented, unless God were to alter the conditions of our present state of existence.

Good out of Evil

But God permits no evil in His Kingdom except for purposes of good, and thus He permits scandal for the trial and perfection and crowning of His elect. Like all other evils which He permits, it works for His glory in the virtues of the saints, who are made able to resist and overcome and win for themselves rewards throughout all eternity which otherwise would not be theirs.

Thus there is this kind of necessity also about the existence of scandals, that they are what God has resolved to permit for the sake of turning them to good by using them for the perfection of the elect. The cruel treatment and persecution which His servants receive, and which seem to proclaim to the world that God has no care for those who serve Him, or for the maintenance of justice, tend to make the virtues of those servants more perfect and more conspicuous, and they also lead, in due time, to public and striking chastisement of the wicked.

Thus they give occasion to a fresh imitation and reflection of the character of our Lord, in His humiliations and sufferings, on the part of the saints, and they lead to the ever-recurring manifestation of His justice in the government of the world by vindicating right and punishing wrong.

The scandals caused by bad example, which are the most numerous and destructive of all, of which our Lord seems to be more particularly speaking in this place, and which are more and more mischievous in proportion to the rank, dignity, position, or office of the persons in whom they are seen, are spurs to the virtues and exertions of the saints, whose business it is to shine like lights in the evil world.

They force them to prayer and to the practice of heroic virtues and of the most exact obedience to the Law of God for the sake of reparation, to the organization of religious communities in which He may be perfectly served, and to all the great works of Christian zeal.

Other scandals which flow from the teaching of false doctrine, and which are innumerable, give occasion for the manifestation of the loyalty and devotion of the faithful, for the vindication of the Catholic doctrine by the doctors and saints of the Church, and for the formal definitions of her Councils and Pontiffs.

‘For there must be also heresies, that they who are approved may be made manifest among you.’1

Thus the great treasures of the doctrine of the Church have been unfolded, and are still being unfolded, in considerable measure under the pressure of the opposing forms of falsehood which have risen up, from time to time, in the course of the wanderings of the human intelligence over the field of Divine truth.

Beside this source of scandal, there is another very fruitful cause of evil in the mistakes and imprudences and negligences of good men, especially when in authority. Our Lord permits this for their greater humiliation and for the trial of souls very dear to Him.

A man’s character is that part of his being of which he has often the least consciousness, and, when he is in authority and in constant contact with a thousand persons and affairs, his faults of character, narrowness, timidity, jealousy, precipitateness, and the like, may sometimes affect the progress of the Church in his own country for a whole generation, and long after.

The world is, in truth, full of snares, according to the vision of St. Antony, and the time will never come when these evils are altogether uprooted.

Strong denunciation of punishment

Thus much, then, may be said, as to the necessity of scandals coming, of which our Lord here speaks. We need not add many words as to the strong denunciation of punishment on the man by whom the scandal comes.

Although scandal may sometimes be given unwittingly, and by men who have no evil intention, still even in those cases it is something diametrically hostile to the work of God in the world, and to the interests of His Kingdom. He it is Who has made scandal possible by placing men in society, and giving to each one what the Scripture calls a commandment concerning their neighbours, mutual duties, and far penetrating influences.

Our dependence one on another gives its power to the evil tongue, or the licentious example, or the personal influence which enchains the will by love or by fear, when the conscience is still inclined to resist.

It is because we live so much by faith one in another, that we are so liable to be led astray to our destruction by the false statement, the historical calumny, the garbled quotation, the crafty perversion of facts, the insinuation of motives.

The temper of children is inculcated in the Church, and it is this temper that is taken advantage of by those who mislead the little ones, who are still uppermost in the mind of our Lord. Moreover, He was speaking to His Apostles, and therefore He must have had in His thoughts the peculiar responsibilities of their great commission in the Church, in consequence of which they, or those who came after them, might be guilty of the sin of scandal, not only by what they said and taught, but also by what they did not say and teach.

Who shall count up, even in thought, the effects of omission of duties and neglect of opportunities, on the part of Apostolic men?

How sins are visited

It runs generally through the whole doctrine on this subject, that a sin committed in consequence of scandal is to be visited on him who commits it, and also on him who has caused it to be committed.

Of course this is especially true of those who are put in authority and who have the commission to teach, and the punishment is to fall on them when they have failed in their duty of warning others, as well as when they have positively taught what is evil. The sentence is repeated more than once in the passage in the Prophet Ezechiel, where this matter is handled.

‘If when I say to the wicked thou shalt surely die, thou declare it not to him nor speak to him, that he may be converted from his evil way and live, the same wicked man shall die in his iniquity, but I will require his blood at thy hand. But if thou give warning to the wicked, and he be not converted from his wickedness and from his evil way, he indeed shall die in his iniquity, but thou hast delivered thy own soul.’2

If silence and forbearance in the case of evil is severely to be punished, it is natural to expect great chastisements of those who make themselves positively instruments of evil.

The first to give scandal was the evil one in the garden of Paradise, when he said to Eve, ‘you shall not surely die.’ And it may truly be said that all who give scandal are the instruments and servants of the evil one, and that their work in the world is nothing else but a continuation of his.

Cutting off hand or foot

Our Lord, therefore, now repeats what He had before said as to the danger of giving scandal.

‘And if thy hand or thy foot scandalize thee, cut it off and cast it from thee. It is better for thee to enter into life maimed or lame than having two hands or two feet to be cast into everlasting fire. And if thy eye scandalize thee, pluck it out, and cast it from thee. It is better for thee, having one eye, to enter into life, than having two eyes to be cast into hell-fire.’

He omits on this occasion the words which He had before quoted from Isaias about the undying worm and the unquenchable flame. But He adds instead a passage which expresses very forcibly the motive already spoken of: the zeal for souls, by which He seeks to supplant in the minds of the Apostles the evil spirit of rivalry, or at least of curiosity about the pre-eminence of this or that one among them in the future Kingdom.

Words about the angels

This, like the passage about the woe to the world because of scandals, is an addition to the former discourse on which this one is in general founded. The first thing which He now says in this connection is that the little ones are watched over with great care by the Angels, who always see the face of the Father Who is in Heaven.

‘Take heed that you despise not one of these little ones, for I say to you, that their Angels in Heaven always see the face of My Father Who is in Heaven.’

There seems no reason for doubting that these words about the Angels who always see the face of the Father Who is in Heaven, signify that this is the reason why we are to take heed not to despise any single one of the little ones.

The reason is, that their Angels have the privilege of immediate access to God, and will be made enemies by any who despise the little ones.

Such an injury puts in exercise their prayers and complaints to His justice, against those who despise and consequently neglect them, as they are ready to move Him also to mercy on those who care for them and help them.

Thus, in the case of the wicked man mentioned in the passage lately quoted from Ezechiel, the Guardian Angel of the person warned, or not warned, by the prophet, might either represent, as an excuse for his charge, that he had not been warned, or as a reason for a reward to the prophet, that he had been warned.

Thus the Angels are not actuated by desire of revenge, when they represent to God the neglect or contempt of their charges on the part of those who are bound to labour for them and care for them. They plead that neglect and contempt as an excuse for the little ones, who might not have gone astray if other measures had been used in their regard, and this simple pleading for the neglected souls is a terrible accusation against those who are guilty of the neglect, being themselves bound to diligence and charity towards them.

This then is the first reason given by our Lord in this place for the care of the little ones. They have most powerful friends and protectors who always see the face of the Father. They would not have these unless they were worth very much indeed in the estimation of God Himself, unless they were very dear to Him Who has created them after His own image.

The end of Our Lord’s coming

Thus much might be said of them, even if they had no part in the still greater work of God, the work of His redeeming love, which goes beyond even the love of the Creator.

But our Lord adds this also: ‘For the Son of Man is come to save that which was lost.’ He does not mean that the guardianship of the Angels over the little ones is on account of the coming of the Son of Man on His mission of salvation, but that that mission of His gives the little ones a fresh dignity and a fresh claim on the consideration of those who understand His character, and who even share and inherit the work of redemption which He began.

Thus the little ones have a dignity, on account of their relation to God, the Creator and the Judge, and also a further dignity on account of their relation to God, the Redeemer. And then He puts this into a parable, of which, as we shall see, He was very fond, because it represents Himself in the character of the Good Shepherd.

‘What think you? If a man have an hundred sheep, and one of them should go astray, doth he not leave the ninety-nine in the mountains, and goeth to seek that which is gone astray? And if it be that he find it, Amen I say to you, he rejoiceth more for that than for the ninety-nine that went not astray. Even so it is not the will of your Father Who is in Heaven that one of these little ones should perish.’

Where there is, for the time, greater danger, there there is always greater anxiety, and more urgent exertion, as in the care of a sheep which has gone astray as compared with that of the remainder of the flock, which is safe in the fold. Those which are safe can be left, and the one which is astray must be sought. And when the search has proved successful, there is greater joy over the recovered one than over the rest which have not had to be recovered, for in that case there has been special risk, particular exertion, continued uncertainty, the excitement of a search and a pursuit, and then the final achievement of success at the cost of labour.

Pre-occupation of the Sacred Heart

All these enhancing circumstances, our Lord tells us, are to be found in the case of the little ones of whom He is speaking. He does not speak of children alone, for all those who are either astray or not safe within the fold, are the subjects of this anxiety and of this labour on His part.

And He wishes all such to be the objects of the loving labours and zealous exertions of the Apostles and of all who are to take their place in the Church. They are not dearer than others, but there is more tender anxiety about them on account of their greater danger. This is enough to make them the darling pre-occupation of the Sacred Heart.

He adds, in the last place, that even His own love for them is inspired by the special care and predilection of the Eternal Father for them. ‘Even so, it is not the will of your Father Who is in Heaven that one of these little ones should perish.’ The Heart of our Lord learns Its special devotion from the will of the Father, and the hearts of apostolic men are to catch their inspiration from the Heart of our Lord.

How the Apostles were answered

We seem to be a long way, with these words and thoughts before us, from the immediate occasion of this outpouring of the affections of the Sacred Heart with regard to the little ones of the flock.

But this is in truth the answer of our Lord to the questionings of His disciples among themselves who should be greater.

It was, as has been said, a question which it was not wise or decent for them to move. At the best, it was a foolish piece of curiosity, which could only serve to dissipate their minds and take them away from the serious work of preparation for the apostolic ministry, and especially for the coming trial of the Passion.

It is well known how mischievous any curiosity is for all the exercises of the spiritual life. It is inconsistent with interior peace, and therefore with the spirit of prayer. It is like a newspaper or a novel as a preparation for Mass or meditation or office.

But in the case before us, it was far more than a bit of mischievous dissipation in its effects on the minds of the Apostles. It stirred the depths of their hearts with the movements of ambition and jealousy, and it confirmed the false conception from which it sprung, as to the nature of the Kingdom itself, of its work, its order, its prizes, and dignities.

The Kingdom which He came to found was indeed to have its external organization, its subordination of officers and rulers and subjects. There were to be some who were to occupy the highest external rank, there were to be places of honour in it which were to be given to those for whom they were prepared by the Father. With all this, the disciples had nothing to do but to wait for the declaration of the Father’s will at the time chosen by Himself.

There was indeed a kind of rudeness and impertinence in peering into arrangements of Providence in these matters, which belong to the secret wisdom, the free choice and counsels of God, as to all matters of personal vocation. And it is for this reason, as well as that of the mischief which results to souls when curiosity is indulged in to any serious extent, that speculations of this kind are so much discouraged in religious communities and by the masters of the spiritual life.

But our Lord, in His extreme tenderness and consideration, did not rebuke them so strongly as He had rebuked St. Peter, in a somewhat similar case, when he had taken on himself to remonstrate with his Master about the future Passion. He evaded the direct question. For what they practically wanted Him to tell them was whether Peter or John or someone else was to be first among them in honour and dignity, as the High Priest was first at Jerusalem.

As to this foolish question, our Lord said nothing, and the only rebuke which He administered to them was contained in the positive and most salutary teaching about the necessity of humility for themselves, and, in the second place, the immense importance of the work to which they were all alike called.

Character of the Kingdom

It is in this that our Lord’s treatment of the disease which had begun to work in their souls consisted.

The Kingdom of God was to be a kingdom founded on humility, built up in humility, and crowned by humility. It was to be a kingdom which had an immense work to accomplish, the salvation of the world. The least and weakest of those for whom its labours were to be spent were immensely dear to God.

Those who received them received Himself and the Father Who sent Him. Where was there room for discussions about the dignity of the labourers, when the very poorest child in the Church represented our Lord and His Eternal Father?

The work they had to do was moreover most delicate and dangerous, a work in which it was easy to make mistakes, to fail even unwittingly, to do immense harm even without intending to do anything but good. It touched the spiritual issues on which the eternity of souls depends; it had to be accomplished in a short time, in the face of most watchful enemies, and at tremendous risks.

The will of the Father was involved in its success. It was the very motive which had brought the Eternal Son down from Heaven, which had governed the whole economy of His life of toil and suffering, a life which was to be soon ended by the Sacrifice of the Cross.

The souls whose salvation was at stake were watched over by angels who could feel the very slightest wrong or neglect or contempt with which their charges were treated, and who would let no indifference to their welfare pass without the liveliest protest before the throne of God.

No fate could be worse than that which would fall on those who injured the little ones of the flock, as to their eternal interests, and injured indeed those interests might be, by the ambitions and contentions of the servants employed to aid them.

Could the hearts and minds of the Apostles once burn with true ardour for the souls over whom they were all called to watch, and take in fully the overwhelming importance of their work, there would be no room left in them for the trivial questionings with which they had been occupying themselves.

Our Lord’s object

Thus, then, it seems to have been our Lord’s object at this time to put these thoughts before them, not without the salutary accompaniment of the solemn warnings of danger to themselves which are here added, rather than to meet their question in any other way either of direct answer or of sterner reproof.

As far as can be gathered, there was no more discussion of this particular question of primacy among them for some considerable time, though it came up again in the request of the mother of the two brothers, James and John, the holy Salome, that her children might have the promise of sitting on our Lord’s right and left hand in His Kingdom.

Then again our Lord baffled the question and turned the thoughts of the ambitious brethren most forcibly to the labours and dangers and sufferings of their calling. Far enough, indeed, even then, they were, from the idea of their office which we find, as has been said, in St. Paul, as in the passage in which he compares himself and his brethren to the combatants in the arena who had no issue from it but by death.

‘For I think that God hath set forth us Apostles, the last, as it were men appointed unto death, because we are made a spectacle to the world, and to angels, and to men. We are fools for Christ’s sake, but you are wise in Christ. We are weak, but you are strong. You are honourable, but we without honour. Even unto this hour we both hunger, and thirst, and are naked, and are buffeted, and have no fixed abode. And we labour, working with our own hands. We are reviled, and we bless, we are persecuted, and we suffer it, we are ill-spoken of, and we entreat, we are made the refuse of the world, the off-scouring of all even till now.’3

From Fr Coleridge, The Preaching of the Cross, Part I

Further Reading:

See also The Father Coleridge Reader and The WM Review’s Fr Henry James Coleridge SJ Archive

Follow our projects on Twitter, YouTube and Telegram:

1 Cor. xi. 19.

Ezech. iii. 18, 19.

Cor, iv. 9-12.